Part 5. App Composition

We continue the series of posts and experiments about explicit software design. Last time we implemented the infrastructure for the application and connected it to the application core’s output ports. In this post, we’ll talk about composition, assemble the converter from its components, and discuss various types of testing.

Building “Bottom-Up”

We will be building the application from its components “bottom-up.” We already have use cases, infrastructure services, and a certain number of UI components. From these, we can build a feature.

I cannot give a clear definition of a feature, but to explain roughly, a feature is a set of functionality that distinguishes a bounded context. You could say that a feature is a “microservice” that handles the work of a particular part of the domain.

Scott Wlaschin has a great diagram in his book “Domain Modeling Made Functional”, which I think is the closest to how I understand features. In his view, the composition of the application looks like this:

Functions we can combine in services:

[low-level operation] >> [low-level operation] => [service]

Services into processes:

[service] >> [service] >> [service] => [use case]

Combining processes in parallel, we get an application:

[use case]

[use case] => [application]

[use case]In my view, there is one more step missing before the final step:

Functions we can combine in services:

[low-level operation] >> [low-level operation] => [service]

Services into processes:

[service] >> [service] >> [service] => [use case]

Combining processes from 1 bounded context, we get a feature (part of an app):

[use case]

[use case] => [feature]

[use case]

Combining features, we get a full application:

[feature]

[feature] => [application]

[feature]Actually, the converter is a “feature.” It contains a set of 3 use cases that are logically related (i.e. through the domain), combined into a single bounded context (currency conversion rules).

“Update Value” Use Case Composition

The function updateBaseValue, which implements the UpdateBaseValue input port type, is currently responsible for the use case of updating the base currency value. To attach infrastructure and UI to it, we’ll use a hook.

First, let’s create the useUpdateBaseValue hook, which will provide the functionality of the use case to the components (inject the use case):

// core/updateBaseValue.composition

export const useUpdateBaseValue: Provider<UpdateBaseValue> = () => {

// ...

};Then let’s remember what dependencies this use case needs:

type Dependencies = {

readConverter: ReadConverter;

saveConverter: SaveConverter;

};…And gather the actual instances of all the required services:

// core/updateBaseValue.composition

export const useUpdateBaseValue: Provider<UpdateBaseValue> = () => {

const readConverter = useStoreReader();

const saveConverter = useStoreWriter();

// ...

};We can now pass these services to the use case function:

// core/updateBaseValue.composition

export const useUpdateBaseValue: Provider<UpdateBaseValue> = () => {

const readConverter = useStoreReader();

const saveConverter = useStoreWriter();

return (value) => updateBaseValue(value, { readConverter, saveConverter });

};Finally, to avoid unnecessary re-renders, we’ll use useCallback:

// core/updateBaseValue.composition.ts

export const useUpdateBaseValue: Provider<UpdateBaseValue> = () => {

const readConverter = useStoreReader();

const saveConverter = useStoreWriter();

return useCallback(

(value) => updateBaseValue(value, { readConverter, saveConverter }),

[readConverter, saveConverter]

);

};…And create the public API for the module:

// core/updateBaseValue/index

export * from './updateBaseValue.composition';Hooks as a Way of Composition

We can notice that we use the hook only as a means of composing the use case. That is, we do not keep application logic in it, but only the logic of interaction between modules.

In a hook, we describe which dependencies need to be created, where to pass them, and what interface the function should provide as a result. With a stretch, we can say that we use hooks as a “poor man’s DI container.”

A “DI container” because it frees the application code from the need to worry about its composition with other modules. “Poor man’s” because we have to do a lot of the work manually: calling hooks of the necessary services, injecting dependencies into the use case, and so on.

The problem with this “container” is that the composition code will be executed at runtime. This check will be executed on every re-render of the hook, and we would like to avoid that:

useCallback(

(value) => updateBaseValue(value, { readConverter, saveConverter }),

[readConverter, saveConverter]

);And in general, the code doesn’t look like code from a standard React application. But if we look at its equivalent in a more conventional form, we would realize that in “standard” hooks, we would have done the same thing, just less explicitly.

More Conventional Hook

The composition with dependency injection that we wrote above is a result of our desire to keep the core of the application independent of libraries and third-party tools.

While this is valid from an experimental perspective, it may not always be reasonable in real projects. In conventional code, it is likely that the use case code itself would be a hook:

export const useUpdateBaseValue: Provider<UpdateBaseValue> = () => {

const model = useConverter();

const saveConverter = useStoreWriter();

return () => {

const baseValue = createBaseValue(rawValue);

const currentRate = lookupRate(model.rates, model.quoteCode);

const quoteValue = calculateQuote(baseValue, currentRate);

saveConverter({ baseValue, quoteValue });

};

};The idea remains the same, we only sacrifice the independence of the application core from tools and mix composition with logic for convenience.

In general, there is nothing terrible about such a compromise, as long as we take into account the direction of dependencies, loose coupling, first-class reliance on abstractions, and functional core approach. This way, the code will be extensible and debuggable.

In the end, even in the “conventional hook” code, it is visible where we prepare dependencies and where the use case begins:

export const useUpdateBaseValue: Provider<UpdateBaseValue> = () => {

// Prepare dependencies and data.

// (Impure section.)

const model = useConverter();

const saveConverter = useStoreWriter();

// Declare the use case function.

// Implement the input port type,

// so that the components are decoupled

// from the application core.

return () => {

//

// Transform the data.

// (Pure section.)

const baseValue = createBaseValue(rawValue);

const currentRate = lookupRate(model.rates, model.quoteCode);

const quoteValue = calculateQuote(baseValue, currentRate);

// Call the service to save the model.

// (Impure section.)

saveConverter({ baseValue, quoteValue });

};

};If necessary, such a hook can be split back into “independent core” and “composition,” because we have taken into account all the limitations in its implementation. This rule can even be used as a mental linter when writing conventional hooks: if we can extract a function with business logic outside, pass dependencies to it, and it works, then the hook is well-written.

If desired, this hook itself can also be decoupled from specific implementations such as useStoreWriter, useStoreReader, and useConverter. I won’t go into detail about this in the text, but I’ll leave a link to an example where I describe different ways of composing the use case in hooks.

Moving on in the text, we will agree to use the first option (with explicit dependency injection in the use case), solely to make the composition ideas more visible and clear.

Connecting Use Case to UI

We have connected the use case with the infrastructure, now let’s connect everything with the UI layer. First, we’ll update the dependencies of the component with the base currency field and indicate that we’ll be accessing the use case through a hook:

type BaseValueInputDeps = {

useUpdateBaseValue: Provider<UpdateBaseValue>;

useBaseValue: SelectBaseValue;

};Since the use case itself and its type remain unchanged, inside the component we just need to access the function. No other code changes will be required:

export function BaseValueInput({ useUpdateBaseValue, useBaseValue }: BaseValueInputDeps) {

const updateBaseValue = useUpdateBaseValue();

// ...The rest of the code stays untouched.

}While the logic of the component and its interaction with the application’s input port remains the same, only their composition has been updated—that is, how we combine them and with what tools. Previously, we passed the use case function directly through props, and now we use a hook to “inject” this function.

The benefit of starting the design from the domain is that it allows us to compose the application in different ways depending on the task, making the interaction between modules more flexible.

After changing the public API of the component, all we have to do is update the tests. Again, since the essence of the component’s work has not changed, we only need to adjust the composition of the hook in the tests:

const updateBaseValue = vi.fn();

// New line:

const useUpdateBaseValue = () => updateBaseValue;

const useBaseValue = () => 42;

const dependencies = {

// Update dependencies:

useUpdateBaseValue,

useBaseValue

};

// ...The test stays the same.Component “Registration”

The last thing we need to do is create a wrapper with a “public API” in the component module. This wrapper will take on the responsibility of connecting all the necessary dependencies in the component and providing its “production version” with already connected dependencies to the outside world:

// ui/BaseValueInput.composition

// Import it so that the real name

// could be re-used in this file later:

import { BaseValueInput as Component } from './BaseValueInput';

// Import real versions of dependencies for the component:

import { useUpdateBaseValue } from '../../core/updateBaseValue';

import { useBaseValue } from '../../infrastructure/store';

// “Register” the component with the same name

// but without requirement for the dependency props:

export const BaseValueInput = () => Component({ useUpdateBaseValue, useBaseValue });Here, we are building a facade over the internal implementation, which is not relevant to neighboring modules. All required dependencies of the component are obtained just before entering the public API. External modules are not aware of these dependencies, and therefore the coupling between them will not increase.

Let’s add the re-export of the component and declare what exactly in this module is the public interface:

// ui/BaseValueInput/index.ts

export * from './BaseValueInput.composition';More Conventional Component

As with the “unconventional hook,” the code of the component does not look like a typical React component, and the point here is also in explicit composition. In fact, hook imports in the component can also be directly specified in the implementation code and used like this:

import { useUpdateBaseValue } from '../../core/updateBaseValue';

import { useBaseValue } from '../../infrastructure/store';

export function BaseValueInput() {

const value = useBaseValue();

const updateBaseValue = useUpdateBaseValue();

// ...

}The difference will be the same as with the hook: we sacrifice weak coupling in favor of convenient imports and lack of additional code. In real projects, we are more likely to see this kind of code.

Tests for such a component will probably mock hooks and services. The coupling between the component and the application core and infrastructure will be slightly higher but the amount of “glue code” will be much smaller.

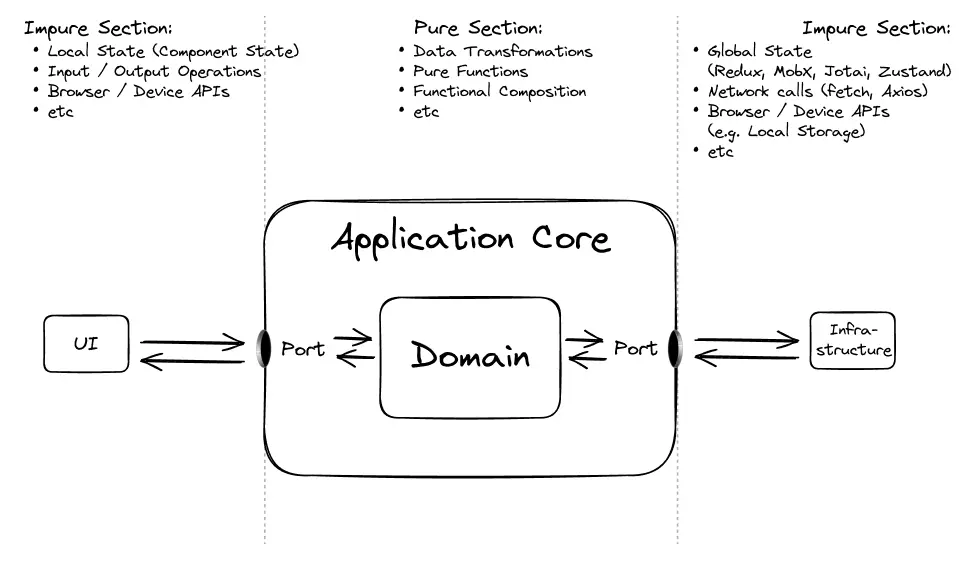

DI, Side Effects, and Functional Core

The just-created use case and its processes lean towards functional programming and repeat the Impureim sandwich we discussed earlier. All side effects are gathered on its edges (in the UI and infrastructure) while pure domain functions that deal only with data transformation reside in the core.

At the same time, we use concepts such as dependencies, DI, “registration,” etc. It may seem like we’re contradicting ourselves since there can be no dependencies in FP, but in reality, we use these concepts precisely on the edges of the sandwich—where side effects live.

If you take a closer look at the layout of the use case, you will see that its core is assembled as a set of sequential calls to several functions. Such composition is functional. In the core of the use case, we do not use the concept of “dependencies,” only input and output data.

However, at the edges, we are still forced to work with side-effects: read data from a field, display information on the screen, update the store. It is at this point, outside, that we use “impure” and “non-functional” techniques. This is a compromise, but we allow it for the sake of convenience in composition.

In terms of ideas, if we discard all the “patterns” and the so-called “DI,” we still follow the tenets of functional programming, namely wrapping pure transformations in an impure context, which provides all the necessary data.

“Refresh Rates” Use Case Composition

Now let’s discuss asynchronous processes. In order to compose the use case of updating quotes, we will also wrap it in a hook:

// core/refreshRates.composition

export const useRefreshRates: Provider<RefreshRates> = () => {

const readConverter = useStoreReader();

const saveConverter = useStoreWriter();

return useCallback(

() =>

refreshRates({

fetchRates,

readConverter,

saveConverter

}),

// No need to watch over `fetchRates`

// because it won't change.

[readConverter, saveConverter]

);

};However, in the component dependencies, we see a different return value:

type RefreshRatesDeps = {

useRefreshRates: () => {

execute: RefreshRates;

status: Status;

};

};To “befriend” the types of both hooks, we can write a separate adapter that will transform the hook returning an asynchronous function into a hook returning this type.

Writing an adapter for the hook

To do this, we need a higher-order function. Higher-order functions take other functions as arguments or return functions as results. In our case, the higher-order function asCommand will take one hook and return another:

// shared/infrastructure/cqs

type Adapted = {

execute: RefreshRates;

status: Status;

};

export const asCommand =

(useRefresh: Provider<RefreshRates>): Provider<Adapted> =>

() => {

const [status, setStatus] = useState<Status>({ is: 'idle' });

const refresh = useRefresh();

const execute = async () => {

setStatus({ is: 'pending' });

await refresh();

setStatus({ is: 'idle' });

};

return { status, execute };

};Next, we can use this adapter to attach to the component the hook that provides the use case:

// ui/RefreshRates.composition

import { RefreshRates as Component } from './RefreshRates';

import { useRefreshRates } from '../../core/refreshRates';

import { asCommand } from '~/shared/infrastructure/cqs';

// Pass as a dependency not the use case hook

// but its “adapted” version.

export const RefreshRates = () => Component({ useRefreshRates: asCommand(useRefreshRates) });Extracting Utility Code

In general, the functionality of the asCommand adapter seems somewhat “utility-like,” because:

- It will likely be necessary to adapt not just one asynchronous process in this way

- The adapter itself does not depend on a specific use case

We can generalize this adapter a bit and get a utility function that we can reuse. First, let’s declare helper types that will explain to other developers what we want to express:

type AsyncFn = (...args: unknown[]) => Promise<unknown>;

type Command<F extends AsyncFn> = {

execute: F;

status: Status;

};Next, let’s extract a higher-order function that will use it:

// shared/infrastructure/cqs

export const asCommand =

<F extends AsyncFn>(useHook: Provider<F>): Provider<Command<F>> =>

() => {

const [status, setStatus] = useState<Status>({ is: 'idle' });

const command = useHook();

const execute = async () => {

setStatus({ is: 'pending' });

await command();

setStatus({ is: 'idle' });

};

return { status, execute } as Command<F>;

};Since the working principle has not changed, there is no need to update the places of use.

Handling Errors

Asynchronous workflows are unreliable. An error can occur during their execution, and we would like to catch it and (for now just) tell the user about it.

Let’s expand the Command<T> interface and add handling for different cases: success and error.

type Command<F extends AsyncFn> = {

execute: F;

result: Result;

};

type Status = Result['is'];

type Result = { is: 'idle' } | { is: 'pending' } | { is: 'failure'; error: Error };Now let’s update the adapter:

export const asCommand =

<F extends AsyncFn>(useHook: Provider<F>): Provider<Command<F>> =>

() => {

// Add local state for an error:

const [status, setStatus] = useState<Status>('idle');

const [error, setError] = useState<Nullable<Error>>(null);

const command = useHook();

// Add `try-catch` and naive error handling:

const execute = async () => {

setStatus('pending');

setError(null);

try {

await command();

setStatus('idle');

} catch (error) {

setError(error as Error);

setStatus('failure');

}

};

// Update the result so that it implements the `Command<T>` type:

const result = status === 'failure' ? { is: status, error } : { is: status };

return { result, execute };

};Now we need to update the component and tests because we’ve changed the interface it depends on:

export function RefreshRates({ useRefreshRates }: RefreshRatesDeps) {

// Destructure the result

// to get required properties:

const { execute, result } = useRefreshRates();

const pending = result.is === 'pending';

// ...

}In tests:

// Change the stubs' types:

const idle: Result = { is: 'idle' };

const pending: Result = { is: 'pending' };

describe('when in idle state', () => {

it('returns an enabled button', () => {

// Update dependencies:

const useRefreshRates = () => ({ result: idle, execute });

// ...The rest of the test code is the same.

});

});Now we can render an error message below the button:

export function RefreshRates({ useRefreshRates }: RefreshRatesDeps) {

const { execute, result } = useRefreshRates();

const pending = result.is === 'pending';

const failure = result.is === 'failure';

return (

<>

<Button type="button" onClick={execute} disabled={pending}>

Refresh Rates

</Button>

{failure && <span>{result.error.message}</span>}

</>

);

}…And cover it with tests:

const failure: Result = {

is: 'failure',

error: new Error('Test error.')

};

describe('when in failure state', () => {

it('returns a message error', () => {

const useRefreshRates = () => ({ result: failure, execute });

render(<RefreshRates useRefreshRates={useRefreshRates} />);

const button = screen.getByText(/Test error./);

expect(button).toBeDefined();

});

});Feature Composition

After we’ve prepared all the use cases, we can compose the converter from them.

The converter component will be the “entry point” to the feature and will gather other components inside it, which are entry points to the use cases:

// ui/Converter

import { BaseValueInput } from '../BaseValueInput';

import { QuoteSelector } from '../QuoteSelector';

import { RefreshRates } from '../RefreshRates';

export function Converter() {

return (

<form>

<BaseValueInput />

<QuoteSelector />

<RefreshRates />

</form>

);

}We can think of this component as the “public interface” of the feature that is available to the outside world.

Note that the components used no longer need to pass any dependencies through props, because this was done during their composition.

Despite the fact that in the near-functional approach we try to keep dependencies explicit, when presenting some functionality “outside” the module, we hide dependencies. For example, Scott Wlaschin, in “Domain Modeling Made Functional”, recommends doing this in such a way:

- For functions issued as public APIs, we hide dependencies from their consumers

- For internal functions of the module, we express dependencies explicitly

Next, we attach a provider for the store and ErrorBoundary:

// ...

import { StoreProvider } from '../../infrastructure/store';

import { ErrorBoundary } from '~/shared/ui/ErrorBoundary';

export function Converter() {

return (

<ErrorBoundary>

<StoreProvider>

<form>

<BaseValueInput />

<QuoteSelector />

<RefreshRates />

</form>

</StoreProvider>

</ErrorBoundary>

);

}…And “register” this component as the public API for the module:

// ui/Converter/index

export * from './Converter';

// features/converter/index

export * from './ui/Converter';Folder Structure and Architecture

So far, we haven’t paid much attention to the folder structure in the project. I intentionally didn’t focus on this because the folder structure is not as important as the interaction between the parts of the system.

I would even say that the project structure is the product of how the modules communicate with each other, what data they share, and how dependencies are organized.

I like to think that the “right” project structure is the one that has evolved as a result of evolutionary design. That is, the one that reflects the real relationships between the modules.

This approach may seem excessively “frivolous,” but I consider it an advantage. Because if we choose a strict folder structure in advance, at the very beginning of the project, when we know almost nothing about it, it can become an unnecessary limitation that will hinder making certain decisions.

In our case, the current folder structure resembles Feature-Sliced Design:

src/

We store features in separate folders

to prevent coupling between them.

(We will discuss this in more detail in the upcoming posts.)

features/converter/

The core of the application (domain, use cases, and ports)

is located in the `core` folder.

Files in this folder can be easily restricted

from importing anything other than the domain and ports,

for example, by a linter.

core/

domain/

refreshRates/

updateBaseValue/

changeQuoteCode/

ports.input.ts

ports.output.ts

Application components are in the `ui` folder.

Note that this includes so-called containers

that connect the core with the UI.

ui/

RefreshRates/

UpdateValueInput/

QuoteSelector/

Adapters to services are in the `infrastructure` folder.

Here we make interfaces of third-party tools compatible

and keep knowledge specific to this feature.

infrastructure/

api/

store/

Service implementations are in the `services` folder.

These are utilities, reusable modules

that do not depend on the project's domain.

services/

network/

“Language extensions”, library code, stubs and mocks,

UI kit, reusable components are in the `shared` directory.

This is also where we can store the Shared Kernel.

shared/

kernel.ts

extensions/

infrastructure/

testing/

ui/

This division of features helps, firstly,

to make them as independent as possible,

and secondly, to add, remove, and replace modules

without the need to rewrite or update

a lot of neighboring code.The main difference from FSD, perhaps, is the explicit highlighting of application ports. But again, it is not necessary to make all concepts explicit, we use them only to more clearly demonstrate the idea of composition.

It is important to note that we did not create this structure from the very beginning—it gradually became more complex as needed. You can track its evolution by looking at the project structure during different stages on GitHub.

Integration Testing

After composing the feature, we can write integration tests for it. In these tests, we’ll verify the functionality of the public API of this module, i.e., the Converter component.

Integration tests should be close to “real usage” and interaction between modules. This way, we can reduce test-induced damage and make them more resilient to refactoring.

For brevity, we’ll skip the implementation of the integration tests in the text, as well as the code. We’ve already provided examples of using the React Testing Library in our code, so I think we can skip this part.

Application Composition

At the next level of composition, we have the whole application. In general, if we had multiple features, we would compose a “set of widgets” for these features here and create “pages” or “screens.”

In our case, the application is only one feature wrapped in a layout, so the code will be quite simple:

// pages/Dashboard

import { Converter } from '~/features/converter';

export function Dashboard() {

return <Converter />;

}

// src/App.tsx

export function App() {

return (

<main>

<Header />

<Dashboard />

<Footer />

</main>

);

}It’s important to ensure that no logic or description of complex processes “leaks” into this level. We should compose fully ready-made blocks that can be replaced, removed, and rearranged without rewriting a large amount of code.

E2E Testing

After composing the application, we can write a set of End-to-end tests to verify the integration of different features together and the overall operation of the application.

Such tests are a way to check the application as real users would use it. These tests are especially useful if the application has complex business processes that involve multiple features sequentially or even simultaneously.

E2E tests are usually heavy and require a browser to be deployed, so we keep them separate from integration and unit tests. We will keep such tests next to the pages because pages are the “entry point” to the application for users.

For an example of E2E tests, we can use Playwright. For instance, we can write a test to check that after clicking a button in the converter, the expected values appear:

import { test, expect } from '@playwright/test';

test('refresh rates use case', async ({ page }) => {

const valueInitial = /1 RPC = 0.3 IMC/;

const valueExpected = /1 RPC = 0.98 IMC/;

await page.goto('/');

expect(page.getByText(valueInitial)).toBeDefined();

const button = page.getByRole('button');

await button.click();

await expect(button).toBeDisabled();

await page.waitForResponse('**/rates');

expect(page.getByText(valueExpected)).toBeDefined();

});We won’t dive into the implementation of other E2E tests in detail, as this is the topic for a separate post. However, you can play around with the set of tests for this feature in the source code on GitHub.

Next Time

In this post, we talked about application composition, built the application from its component parts, and touched on different types of testing. Next time, we’ll talk about how to achieve the same thing without hooks, how to inject dependencies “in advance” before runtime, and what potential benefits this approach may have.

Sources and References

Links to books, articles, and other materials I mentioned in this post.

Books

- Clean Architecture by Robert C. Martin

- Code That Fits in Your Head by Mark Seemann

- Domain-Driven Design by Eric Evans

- Domain Modelling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin

- Software Architecture in Practice by L. Bass, P. Clements, & R. Kazman

- Unit Testing: Principles, Practices, and Patterns by Vladimir Khorikov

Architecture and Module Interaction

- The Clean Architecture

- Features, FSD

- Functional architecture is Ports and Adapters

- More than concentric layers

- Organizing App Logic with the Clean Architecture

Dependency Management

Common Patterns

Tools and Methodologies

- Feature-Sliced Design

- Guiding Principles, Testing Library

- Playwright, end-to-end testing for modern web apps

Other Topics

- C0in Е2Е Testing with Cypress

- Higher-order function, Wikipedia

- “JavaScript front-end file structure” instead of “library X file structure”

- Test-induced design damage

- Your Guide to React.useCallback()

Table of Contents for the Series

- Introduction, assumptions, and limitations

- Modeling the domain

- Designing use cases

- Describing the UI as an “adapter” to the application

- Creating infrastructure to support use cases

- Composing the application using hooks (this post)

- Composing the application without hooks

- Dealing with cross-cutting concerns

- Extending functionality with a new feature

- Decoupling features of the application

- Overview and preliminary conclusions