Domain Modeling Made Functional by Scott Wlaschin

I wanted to read this book for a long time, because I heard a lot of good reviews about it. After reading it, I’m amazed at how many tricks from the book I’ve developed on my own, because it’s really more convenient to develop that way 😃

The book is good. It’s written with an emphasis on practice and good code examples. It’s clear that one book can’t cover every possible system modeling problem, but the author has picked an example that covers a good portion of the most common ones.

Something in the book established the design approaches that I use myself. Something was entirely new. But first things first.

What This Book is About

In the introduction the author writes:

There is an opinion that functional programming is all about mathematical abstractions [and unreadable code]. …I aim to show that functional programming is in fact an excellent choice for domain modeling, producing designs that are both clear and concise

In the book, the author shows how to model the domain using only types and functions. I myself have been using this for a long time. From recent examples: I rewrote Tzlvt using this approach, and I also gave a talk about Clean Architecture on the Frontend. In both cases, the domain is designed in types and functions.

The book is worth reading, says the author, if:

- You’re wondering how you can model using only types and functions;

- You’re wondering why Domain Drive Design and FP are perfect for each other;

- You wanted to learn FP, but were put off by a bunch of math;

- You wanted to look at F#.

The author gives code examples in F#. In the outline, I translated some of the examples into TypeScript so that more readers would understand them. I did not manage to translate everything because F# has features that are not directly translatable in TypeScript. So I recommend to read the book yourself or at least look at the repository with code from this book.

The book itself is divided into three parts:

- Concept of a domain

- Modeling

- Implementation

I split the summary into 3 parts too, otherwise it would have been too big. In this post, we’ll cover the first part of the book. We’ll talk about what this domain is, why you need it, and how to decompose large domains into smaller components that can evolve independently of each other.

In the second post, we’ll discuss, how to design data flow in a functional style, what is the difference from OOP, how types can help document and reflect business requirements.

In the third post, we’ll discuss the implementation of the domain model, using a composition of functions, partial application, and monads. Yup, there will be monads too.

Chapter 1. Introducing Domain-Driven Design

The author begins the chapter by stating that the development team needs some kind of shared model of the domain with which the application is connected.

As an anti-example, he cites a team where business requirements analysis, design, and development are performed by different people. This separation is dangerous because developers may end up not understanding exactly what they are working on. If industry experts, analysts, architects, and developers use different concepts for the same things, the meaning can get very distorted by the end of the “translation.”

Instead, the author proposes to use a generic domain concept. If the concepts expressed by analysts and stakeholders are expressed in the same way in the code, there will be less “translation loss”. This has several advantages:

- Faster development and publication in production: the less divergent the understanding of the application’s objectives, the faster the more appropriate solution will emerge;

- Less garbage: development will spend less time prototyping and failing solutions;

- Easier support: making changes will be easier and safer, new developers will feel more comfortable with the code.

To create this common understanding, the author makes several recommendations:

- Focus on business events and processes, not data structures;

- Split problem domains into smaller domains (subdomains);

- Develop a “ubiquitous language” describing the concepts of the domain, which will be used by everyone associated with the application.

Understanding the Domain Through Business Events

The first rule is “Focus on events, not data structures”. Businesses don’t just work with data, they change and transform it. We can think of business processes as a series of data changes. The essence and value of the business is in those transformations, so it’s important to understand exactly what happens to the data during the changes.

Data changes don’t happen by themselves, something triggers them. The author calls these triggers domain events. The events are the starting point of all the processes we want to simulate in the application. The author suggests recording events in the past tense—“Something happened”.

To define domain events, we can use event storming. Anyone who understands how different parts of the business work can participate. During the storming, participants name and write down what must happen for a process to begin. Then they write down what happens along the way and afterward. Often events will add up from a chain; this will come in handy for us in the future.

In the book, an example would be a kind of “order-taking system”. This is roughly what the first event storming might look like:

— In our department, we process applications.

— What triggers this kind of work in your department?

— We receive an application from customers by email.

— So we can record the event “Application received”.

— We fulfill these orders when they are signed.

— At what point does this happen?

— When we receive an order from the receiving department.

— We can call this event “The order is placed”.

…etc

After a while we will get a list of domain events:

- Order received;

- The order is placed;

- The order is sent;

- New user registered…

Some events “pull” with them workflows like “Place Order”, “Send Order”, etc. The more events we see, the larger processes they will start to add up.

Such a storm is good because:

- Tt creates a common understanding and language of the business for all involved;

- Draws attention to all departments and teams;

- Makes gaps in requirements more visible;

- Illuminates how the output of one department or team becomes the input for the work of another department.

Chains of events in a good way should be long and cover the whole system. The author suggests asking yourself what can happen before the first event and what can happen after the last event to find the missing events.

When the events are gathered, the participants think about what actions led to them. The author calls these actions commands. In the book they are written in the form of a command verb: “Do that”. As a rule, the result of a command is an event:

- Send order → Order sent;

- Register user → User is registered.

An event triggers a command, which initiates some business workflow. The output of the workflow is some more events

As a result, we think of a process as a function with inputs and outputs.

Partitioning the Domain into Subdomains

Usually we solve big tasks by dividing them into smaller tasks—the same with the domain. We can distinguish several parts of the “order processing”: receiving, assembling, shipping, etc. Businesses usually already have different departments for these parts. We will call such parts subdomains.

[Here, a] “domain” in “an area of coherent knowledge” …We will think of it as where the “domain expert” is the actual expert

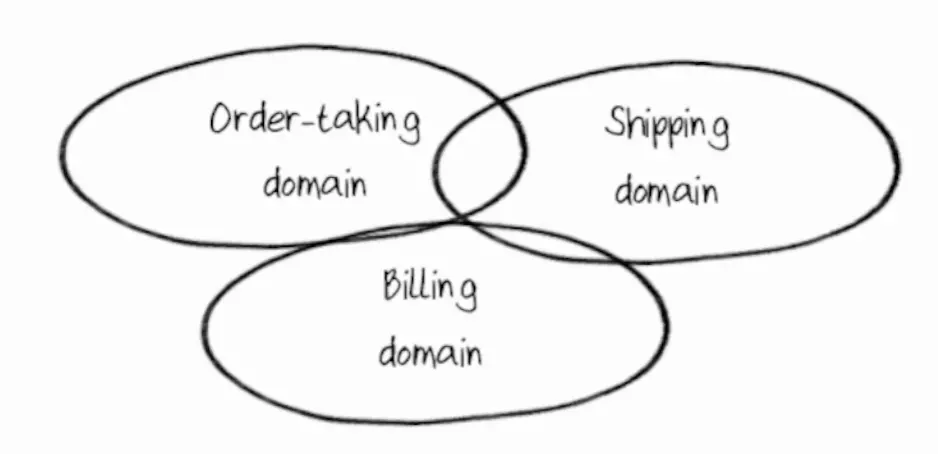

Different subdomains can overlap, this is normal. For example, the receiving department may need to know something about payment or shipping:

To make it easier for developers to understand the processes within domains and subdomains, they need to learn more about these domains and the processes within them.

Creating a Solution Using Bounded Contexts

Understanding a problem doesn’t yet mean solving it, but it does help to find a solution. The solution will not completely and accurately reflect the real world; instead, we will use only information that really will help model the system.

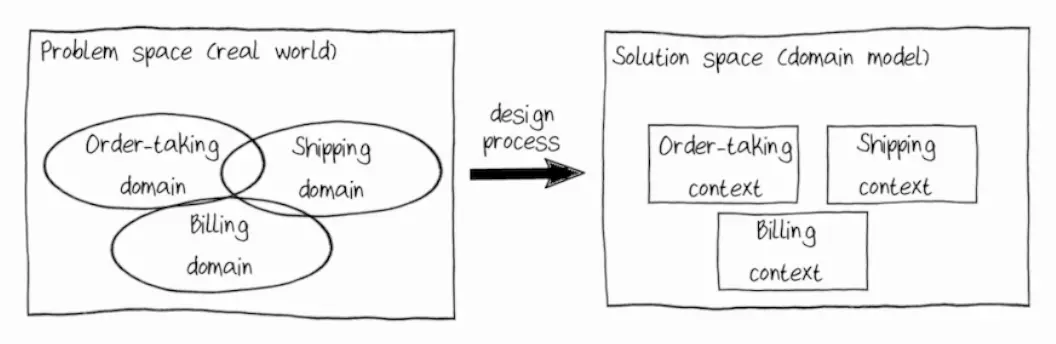

This is where the distinction between “problem space” and “model space” comes in. A model contains only what we need:

In the model, we display domains and subdomains as bounded contexts—parts of the overall model, each of which simulates one subdomain.

Contexts—because within each we use common language and knowledge. Bounded—because they have clear boundaries. In the real world, subdomains overlap, but in the model we try to avoid this to make it easier to implement the model in code. We sacrifice granularity for the sake of code simplicity and better support.

[This means] that our domain model will never be as rich as the real world

Domains and contexts are not always 1 to 1. Sometimes a domain is split into several contexts, or several domains are modeled through one context. It depends on the task. But the important thing is that each context has only one clear responsibility.

Highlighting contexts isn’t easy, a few tips for doing so:

- Listen to domain experts talk; if they speak “the same language,” they probably work in the same subdomain;

- Pay attention to the division by department in the company, this is a good clue as to how the business sees parts of itself;

- Don’t forget that contexts should be bounded;

- Remember, it’s better to make several independent contexts than one super-mega-context that will be difficult to develop.

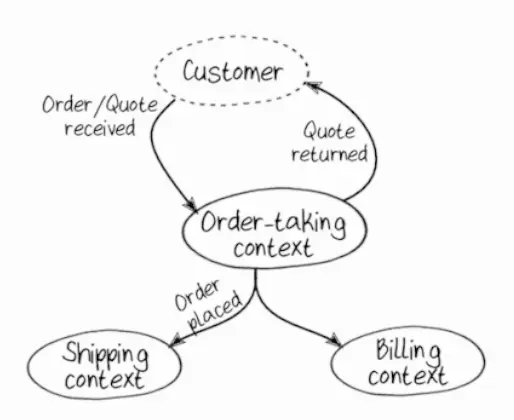

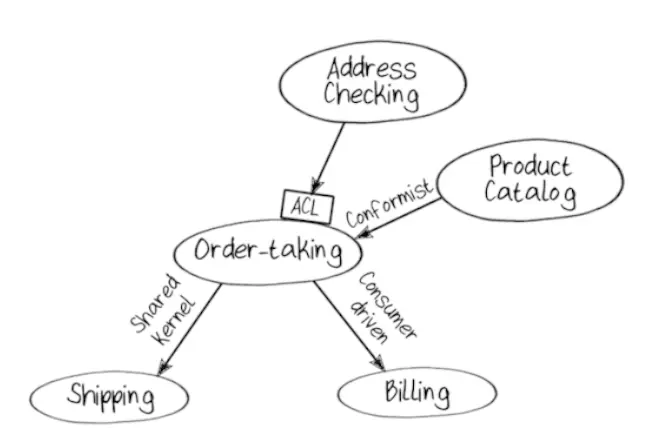

Once the contexts are highlighted, use context maps—diagrams of how these contexts interact. The important thing here is not to specify all the details, but to create a top-level representation of their relationships. For example, the model from the example above can be mapped as such a map:

Some domains are more important to the business and, in fact, make money—these are the core domains. Those that help the core domains work are called supportive domains. Those that are not unique to the business and can be outsourced are generic.

For example, for the company in the example, order-taking may be the core domain, because the company is famous for its customer support. Billing could be a supportive domain, and shipping, which can be outsourced, could be a generic domain.

Creating a Ubiquitous Language

Ubiquitous language will help the team operate with the same words, talking about the same concepts.

This is what we create and use when we design. In this language, we describe concepts with the terms that domain experts use. If someone says “Order,” that’s what we should call the concept in question. And vice versa, there should be no words in the design that are not familiar to domain experts: OrderFactory, OrderMapProcessor, and so on.

Chapter 2. Understanding the Domain

In this chapter we will take one particular work process and examine it in detail:

- What leads to it;

- What data are needed;

- What bounded contexts will be involved, etc.

Interview with a Domain Expert

Try to learn as much as you can from the experts about the inputs and outputs of each process you’re working on. Listen more and ask questions even about the “obvious things”.

You can find out, for example, that the same order form can lead to different processes: the order itself or price calculation without sending the goods. Or that checking product codes will require a product catalog—which may be a separate bounded context. Document everything you hear in the same terms the examiner uses.

Also, define what the workflow is the input. For example, in the “Place Order” process, the input data will be “Order Form”. The output data will always be some events, for example, in the process “Order Placed” such an event may be “Order Placed”.

Fighting the Impulse to Do Database-Driven Design

If you have worked a lot with databases, at this point you may feel the urge to start designing tables. Domain Drive Design (DDD), on the other hand, proposes the principle of persistence ignorance.

If you design for a database, you risk (intentionally or inadvertently) omitting details of the domain in order to fit it to the database. For example, two entities that look similar but are different in meaning may end up in the same table and have different flags. It will be inconvenient to work with them later.

Fighting the Impulse to Do Class-Driven Design

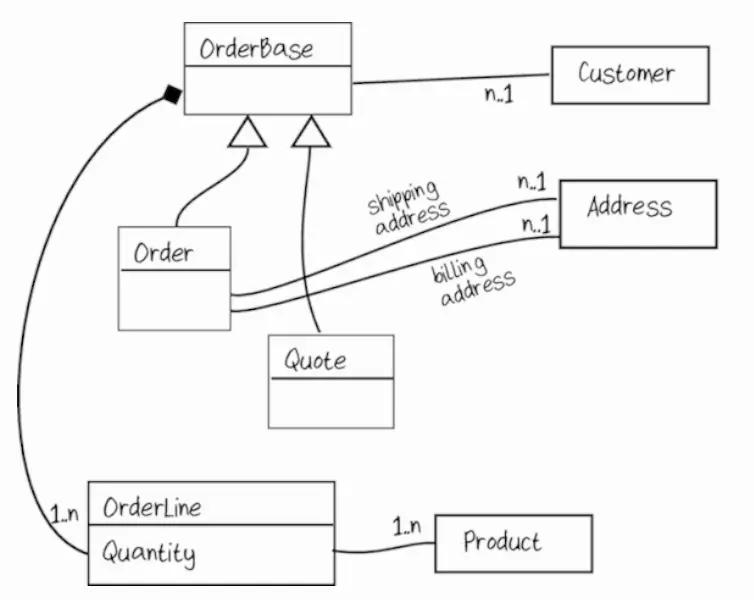

If you have a lot of experience with OOP, you too can fall into the trap of starting to design classes in your head. For example, for the application in the example, you might get something like:

Here, two similar entities Order and Quote are highlighted, but there is some artificial OrderBase in the diagram. The problem is that this OrderBase does not exist in reality. If you want to check—ask a domain expert what OrderBase is.

The moral here is this:

[We should] collect information about the domain carefully and should not mix in technical ideas and details

Documenting the Domain

Instead of tables and classes we will use the language we speak. We will describe processes as a set of inputs, outputs, and side-effects. We will describe “data structures” as enumerations of what should be in that “structure”.

For example, the process of accepting an order will then look something like this:

Process “Accept Order”

Caused by the “Received Order Form” event

Main input data: Order Form

Implicit input data: Product Catalog

Output data: “Order Received” event

Side effects: Notification of acceptance sent.We would describe the data roughly as follows:

data Order =

CustomerInfo

AND ShippingAddress

AND BillingAddress

AND list of OrderLines

AND AmountToBill

ShippingAddress = ???

BillingAddress = ???The point of this format is that it is not scary for “non-programmers”. That is, descriptions of processes and data can be shown and discussed with domain experts. This will allow errors to be detected earlier.

Diving Deeper into the Order-Taking Workflow

When we take apart the business processes in more detail, we can reveal details that were not previously apparent. In the example application, orders will be more important than quotes, because the company gets money for orders, while price requests don’t bring in money.

We can also find out the details of how the process itself goes. For example, we can find out that when we receive an order, the employees first check the client’s name, phone number and address. They may use special programs or services to check the address—which means we have to communicate with external services in this process.

Or we may find out that not all items are sold in pieces, some may be sold in kilograms. So OrderQuantity has to be part of a common language, so that everyone means the same thing.

“It depends.” When you hear that, you know things are going to get complicated

Representing Complexity in Our Domain Model

After refining the process, the model became much more complex. This is good, because it is better to deal with complexity at the design stage than in the middle of a coding sprint. Consider what’s missing now.

We learned that product and quantity codes aren’t just strings and numbers; they have limitations. Let’s add them:

context: Order-Taking

data WidgetCode = string starting with "W" then 4 digits

data GizmoCode = string starting with "G" then 3 digits

data ProductCode = WidgetCode OR GizmoCodeWe use the terms ProductCode, WidgetCode and GizmoCode because domain experts used them in conversation. But isn’t this too specific a description? Won’t the lack of abstractions cause problems in the future?

Generally speaking, it is more important for us to capture and reflect the domain expert’s point of view at this stage. This is not to say that the implementation cannot be abstract, but we should avoid concepts in the model that are not in common language.

Let’s continue to clarify the constraints. In quantity, it’s important for us to specify in what interval values can be. We find this out from domain experts, too:

data OrderQuantity = UnitQuantity OR KilogramQuantity

data UnitQuantity = integer between 1 and 1000

data KilogramQuantity = decimal between 0.05 and 100.00After that, let’s clarify the data structure of the order itself. Right now it does not reflect the life cycle of the order at all. To fix this, we will split the structure into several according to their purpose. For orders that have not yet been validated:

data UnvalidatedOrder =

UnvalidatedCustomerInfo

AND UnvalidatedShippingAddress

AND UnvalidatedBillingAddress

AND list of UnvalidatedOrderLine

data UnvalidatedOrderLine =

UnvalidatedProductCode

AND UnvalidatedOrderQuantity”For validated:

data ValidatedOrder =

ValidatedCustomerInfo

AND ValidatedShippingAddress

AND ValidatedBillingAddress

AND list of ValidatedOrderLine

data ValidatedOrderLine =

ValidatedProductCode

AND ValidatedOrderQuantity”For priced orders:

data PricedOrder =

ValidatedCustomerInfo

AND ValidatedShippingAddress

AND ValidatedBillingAddress

AND list of PricedOrderLine // different from ValidatedOrderLine

AND AmountToBill // new

data PricedOrderLine =

ValidatedOrderLine

AND LinePriceAnd the process result:

data PlacedOrderAcknowledgment =

PricedOrder

AND AcknowledgmentLetterSo we note what needs to be done for the order to go through the whole process. First, to check that the customer’s addresses exist and that the product codes are correct, then to check that each item on the product list has been calculated an intermediate cost and the entire order has been calculated a full cost. As a result, the process will create an accepted order and send an email to the customer that the order has been accepted.

After describing the data, we will describe the process itself:

workflow "Place Order" =

input: OrderForm

output:

OrderPlaced event

OR InvalidOrder

// step 1

do ValidateOrder

If order is invalid then:

stop

// step 2

do PriceOrder

// step 3

do SendAcknowledgmentToCustomer

// step 4

return OrderPlaced event (if no errors)We can refine each step by describing what data and dependencies it needs and what the result will be. For example, a validation step receives an unvalidated order as input and outputs a validated order or a validation error. As dependencies, let’s specify address validation and product codes, because they would require a product catalog or an external address validation service:

substep "ValidateOrder" =

input: UnvalidatedOrder

output: ValidatedOrder OR ValidationError

dependencies: CheckProductCodeExists, CheckAddressExists

validate the customer name

check that the shipping and billing address exist

for each line:

check product code syntax

check that product code exists in ProductCatalog

if everything is OK, then:

return ValidatedOrder

else:

return ValidationErrorAnd so on for each step of this process and other processes.

Chapter 3. A Functional Architecture

In this chapter we will look at the architecture of a program with a function-oriented domain. We will assume that it consists of 4 “levels”:

- The system context is the whole system we are modeling

- It consists of several containers—individual units which can be separately deployed.

- Each container consists of components—the building blocks of the code.

- Each component consists of modules with low-level functions and operations.

Bounded Contexts as Autonomous Software Components

Each context is ideally a self-contained subsystem with clear boundaries. At the beginning of the design, however, we don’t care whether we are going to deploy the project as a microservice or as a monolith. The main thing is to make sure that we keep the contexts decoupled.

Communicating Between Bounded Contexts

Contexts will communicate with each other through events, making them completely decoupled. Events will not just be signals from one context to another, but will also contain the data that the next context needs in order to process the event.

The data we work with within contexts will be called domain objects. The data that we transfer between contexts, though it may look like domain objects, is not domain objects. These would be special data transfer objects, DTOs. Such objects will usually contain the same information, but structured so that the object can be conveniently serialized.

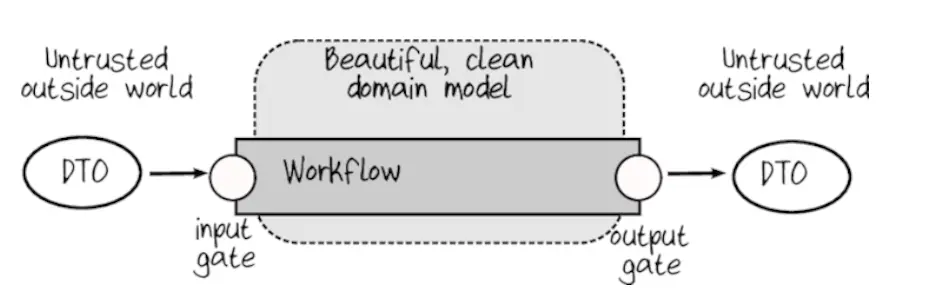

The boundaries of each context will act as gates. Everything that comes to the context from outside is DTO, it has to be checked and validated. After validation we will get domain objects that we can work with as safe data. Validation will be handled by the input gate:

The output gates will check that no unnecessary or sensitive information happens to be in the output. This will improve security and prevent meshing between contexts.

Contracts Between Bounded Contexts

No matter how decoupled the contexts are, communication between them still creates some kind of coupling. To keep it painless, contexts should choose the format of messages they will use when communicating—work out a contract.

Contracts and their choices come in many forms:

- Shared kernel, when two contexts decide to use some common message format.

- Consumer driven, when the consumer decides what message format they want, and the sender adjusts to that format.

- Conformist, when the sender chooses the format and the consumer adjusts to it.

When communicating with external systems, anti-corruption layers (ACL) can be used. These layers translate the data into the formats our system understands and needs. It’s as if we’re adjusting the outside world to ourselves, not the other way around.

In the example application we will use different relationships. Often it turns out that the pattern of relationships between contexts reflects the pattern of interaction between teams in the company:

Workflows Within a Bounded Context

In a functional architecture, each of the workflows is a function whose input is a command and whose output is one or more events. Such workflows are always within the same context and never implement End-to-End processes.

In the output, we have to give only what we really need to the next context, no more. For example, after order acceptance we don’t need to give all information about the order to BillingContext, just the order ID, delivery address and total order amount:

data BillableOrderPlaced =

OrderId

AND BillingAddress

AND AmountToBillAlso make sure that all domain events are result work and do not call other handlers within the process.

Code Structure Within a Bounded Context

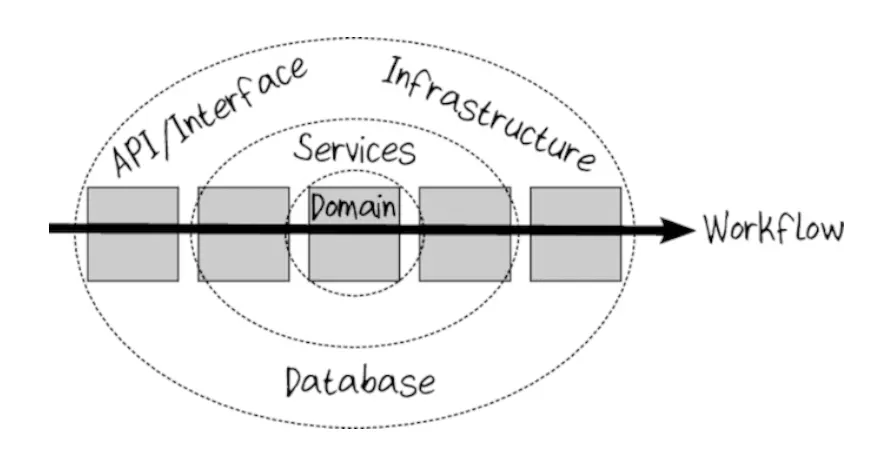

The central part of the context will be the domain, everything else will be located around it. Dependencies will be directed inward, that is, towards the domain. This approach is known as onion architecture:

Our goal is to work with predictable functions. In such functions, we don’t need to look at their internals to understand what they do. For this purpose, we will try as much as possible to use immutable data structures, and we will make all dependencies explicit.

All input and output will be placed at the edges of the onion, at the beginning and the end of the process. Then the root domain logic will be separated from storage, API and infrastructure. This way we will achieve persistence ignorance.

What Next

This time we discussed what domain is and why we need it.

In part 2 we’ll talk about how to design flow of programs in a functional style, what’s the difference from OOP, how types can help document and reflect business requirements. In part 3, we’ll discuss implementing the domain model, using composition and partial application of functions.