C0in Е2Е Testing with Cypress

C0in is an finance management and helper app. In this post, I’ll show how I automate use case testing in it.

Right now it has three important use cases: logging into the app, creating a budget, and recording a spend or income. The logic is covered by unit tests, but that’s not enough. I want to be sure that if the use cases break somewhere, I’ll know about it immediately. That’s why I also write E2E tests for C0in.

Tools

End-to-end (E2E) tests are integration tests that interact with the UI the way a user would. I tried several tools for E2E, but I liked Cypress the most.

After installing and starting, a folder cypress/ appears in the root of the project. Inside it integration/, there are the tests themselves, and support/, there are auxiliary functions (more about this further).

App Login

Login to the C0in app is so far by invitation, and you have to enter the correct code to enter. Therefore, the first use case the user encounters is entering the login code.

The use case has two outcomes: successful and unsuccessful login. Let’s write a test for the first case.

describe('Login window', () => {

it('Valid code passes login', () => {

// Test logic here...

});

});We need to enter the application and get to the login page. We will enter the page with the visit command, passing the address as argument:

// For example, we test the app locally:

cy.visit('localhost:8081');Check if the login form exists, and if the input field is empty. Check if the required blocks exist and if the field is empty:

cy.get('.login').should('have.length', 1);

cy.get('.login-code').should('be.empty');Selecting items in Cypress works similarly to jQuery. For example, here we select elements by class. The method should will check that there is only 1 element with class login on the page, and the element with class login-code is empty.

Typing in real input fields in Cypress is done through the type method. But in C0in, the keyboard is non-native and there are no real input fields there either. Instead there are blocks that show the “typed” sequence. To type some code on our keyboard, you have to “press” the key with the desired digit. We will break the code into characters and press the keys with the specified characters.

The contains method looks for an element that contains the text passed in the argument, in our case a character. The closest method finds the nearest parent with the specified selector, in our case the button class.

const chars = code.toString().split('');

chars.forEach((char) => {

cy.get('.keyboard').contains(char).closest('.button').click();

});When the code is typed, you can press the red button to “send” the code.

cy.get('.button.is-enter').click();The code of the whole test will look like this:

describe('Login window', () => {

it('Valid code passes login', () => {

// Login to the app:

cy.visit('localhost:8081');

// Check the form:

cy.get('.login').should('have.length', 1);

cy.get('.login-code').should('be.empty');

// Enter the code:

const chars = validCode.toString().split('');

chars.forEach((char) => {

cy.get('.keyboard').contains(char).closest('.button').click();

});

// Press Enter:

cy.get('.button.is-enter').click();

});

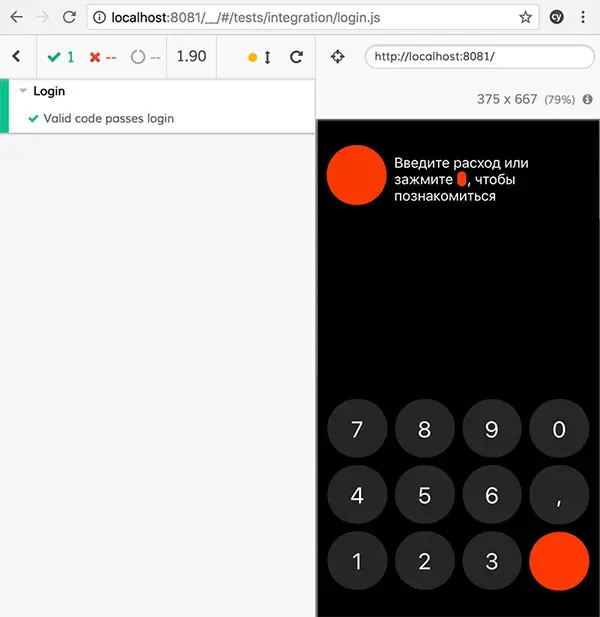

});After launching, Cypress will start the browser, run the script and show whether or not it passed the test. It looks like this:

Refactoring and Second Use Case

Now let’s move on to the test with the wrong code. It will be the same, only the code will be different and the result will be different. In order not to duplicate the code, we can extract the repetitive actions into functions. But Cypress has a more elegant solution: commands.

Commands are like plugins. You describe a function-command, and it becomes globally accessible via cy. The commands are stored in the support/ folder, they can be separated into files however you want. The main thing is to import them into support/index.js so Cypress can see them.

The URL will not change, so we extract the login command into enterApp, and the address itself will be written in fixtures/common.json:

import { baseUrl } from '../fixtures/common.json';

Cypress.Commands.add('enterApp', () => cy.visit(baseUrl));Checking the form will also be repeated, so put it in the appContainsEmptyLoginForm command.

Cypress.Commands.add('appContainsEmptyLoginForm', () => {

cy.get('.login').should('have.length', 1);

cy.get('.login-code').should('be.empty');

});I prefer to name commands with:

- either a verb with an action to be performed:

enterApp; - or a predicate for checks:

appContainsEmptyLoginForm.

The first ones don’t check anything, they just perform some action and produce a side effect. The latter ones check what the name describes.

We will need to input numbers on the keyboard in other tests of the application. So we will turn it into a keyboardType command.

Cypress.Commands.add('keyboardType', (str) => {

const chars = str.toString().split('');

chars.forEach((char) => {

cy.get('.keyboard').contains(char).closest('.button').click();

});

});Pressing “Enter” will also help us in other places:

Cypress.Commands.add('pressEnter', () => {

cy.get('.button.is-enter').click();

});In the end, the test code will look like this:

describe('Login', () => {

it('Valid code passes login', () => {

cy.enterApp();

cy.appContainsEmptyLoginForm();

cy.enterLoginCode(validCode);

cy.get('.login').should('have.length', 0);

});

});Now let’s write a negative test for the wrong code:

it('Invalid codes dont pass login', () => {

cy.enterApp();

cy.appContainsEmptyLoginForm();

cy.enterLoginCode(invalidCode);

cy.get('.login').should('have.length', 1);

});As we can see, the first two lines are the same, so they can be taken to the test set-up:

describe('Login', () => {

beforeEach(() => {

cy.enterApp();

cy.appContainsEmptyLoginForm();

});

it('Valid code passes login', () => {

cy.enterLoginCode(validCode);

cy.get('.login').should('have.length', 0);

});

it('Invalid codes dont pass login', () => {

cy.enterLoginCode(invalidCode);

cy.get('.login').should('have.length', 1);

});

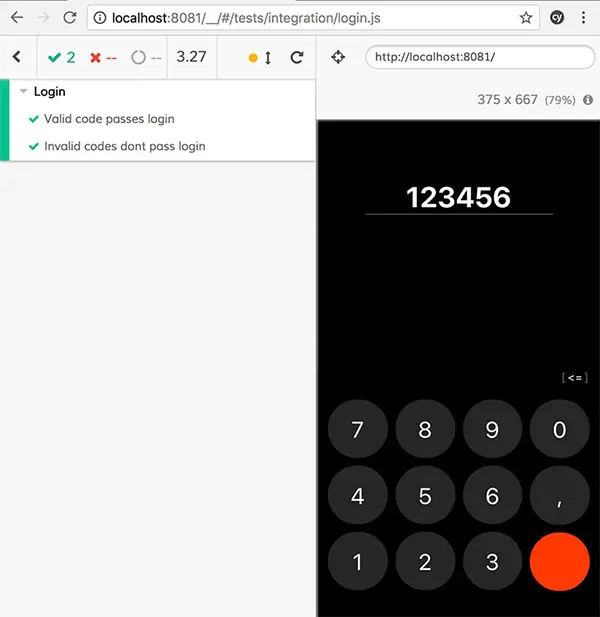

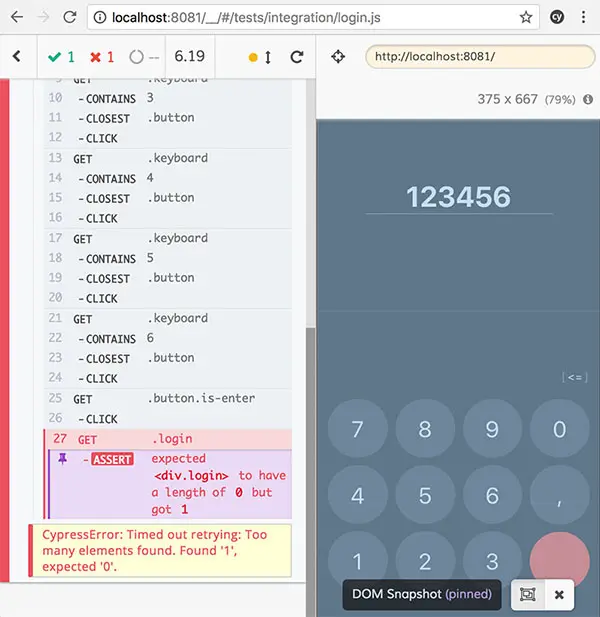

});After launching, we will see the following picture:

If any test fails, the logs will describe what didn’t match. Cypress is awesome at describing the error: it shows which node caused it, what didn’t match, and saves a snapshot of the state. That is, you can click on this bug with your mouse, and on the right side will be shown the state of the page at this time!

Budget Creation Use Case

The second scenario is the creation of a budget. To create a new budget, you need to open settings, enter the amount, days count, and save. Let’s check each step.

Let’s make a budget of 10,000 credits for 10 days. The app will only put 95% of the amount we enter into the budget so that the plan doesn’t come up short. So, after saving, the budget will contain 9500 credits.

describe('Budget creation', () => {

before(() => {

// Command for a quick login to the application, bypassing the form:

cy.login();

cy.enterApp();

// Opens budget settings:

cy.openBudgetSettings();

});

it('Inputs the budget sum and saves it', () => {

cy.keyboardType('10000');

cy.pressEnter();

cy.get('.budget').contains('9500');

});

});Next, we choose a deadline. We will choose 10 days, so we need to highlight the 10th item in the date select. We check that the dates up to and including the selected one became red and that the budget line appeared with the amount per day.

it('Inputs the budget time and saves it', () => {

cy.get('.datepicker-item')

// Indices start with 0, so the 10-th element — eq(9)

.eq(9)

.click();

cy.get('.datepicker-item.has-red-color').should('have.length', 10);

cy.get('.dialogue-secondary').contains('for 10 days. 950 per day');

cy.get('.button.is-fixed-rb').click();

});After saving, we check if the amount for the day is calculated correctly. We will need to check the contents of the counters in other tests as well, so create a command:

Cypress.Commands.add('counterContains', (content) => {

cy.get('.mainContent .dialogue .counter').contains(content);

});

it('Tests todays limit', () => {

cy.counterContains(950);

});And that the record of the history of the creation of the budget was preserved:

Cypress.Commands.add('budgetRecordContains', (sum, days) => {

const $lastRecord = (selector) => cy.get('.timeline').find(selector).last();

$lastRecord('.record--budget').contains(sum);

$lastRecord('.record--budget').contains(days);

});

it('Tests history record', () => {

cy.budgetRecordContains(9500, 10);

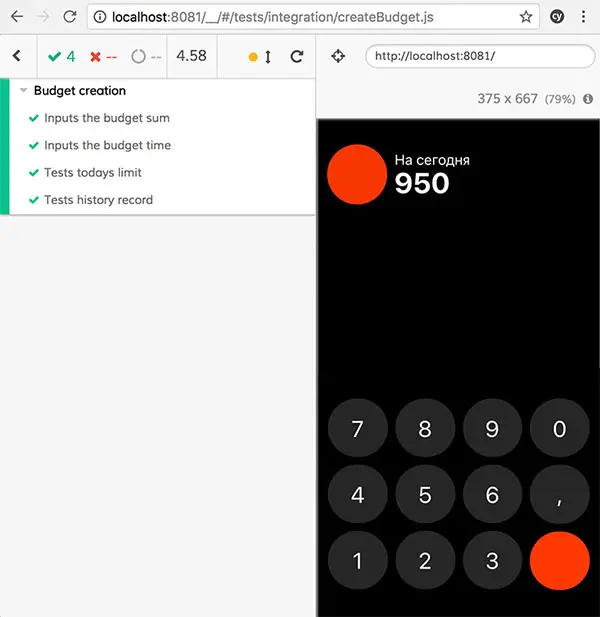

});After launching we will see the following picture:

Basic Spending Use Case

Now let’s check the spending use case. There are two options for spending: when there is no budget yet, and when it is set. To separate the set of tests for the first case from the set for the second, we will use context.

describe('Tests spendings', () => {

context('When budget is not set', () => {

beforeEach(() => {

cy.login();

cy.enterApp();

});

it('Spends 400 credits for helpful stuff', () => {

// ...

});

});

});Each spending we can make helpful or harmful. To check all cases and not to repeat the code, let’s write a function spendMoneyOnce that will deal with spending.

// Command to turn categories on and off:

Cypress.Commands.add('toggleCategory', (type = 'helpful') => {

cy.get(`.category.is-${type}`).click();

});

const spendMoneyOnce = (amount, category = 'unknown') => {

amount = `${amount}`;

cy.keyboardType(amount);

cy.get('.numberDisplay-value').contains(amount);

if (category !== 'unknown') {

cy.toggleCategory(category);

}

cy.pressEnter();

};And a function that will check to see if the spending has been saved:

const spendSaved = (amount, category) => {

// Command to check the last record in the history:

cy.lastRecordContains(amount, category);

};Then testing spending in categories would look like this:

it('Spends 400 credits for helpful stuff', () => {

const [amount, category] = [400, 'helpful'];

spendMoneyOnce(amount, category);

spendSaved(amount, category);

});

it('Spends 400 credits for harmful stuff', () => {

const [amount, category] = [400, 'harmful'];

spendMoneyOnce(amount, category);

spendSaved(amount, category);

});Spending from Filled Budget

Now let’s test spending when the budget is set. I have described many use cases, but here I will show two. In the first one, the spending is less than the daily limit and the amount for the day stays the same, in the second one, the spending is more and the amount for the day decreases.

context('When budget is set, 950 for today', () => {

beforeEach(() => {

cy.login();

cy.enterApp();

// Command for quick creation of a budget with specified parameters

cy.createBudgetWith(10000, 10);

});

it('Spends amount smaller than the limit for today', () => {

testSpendWithActiveBudget({

amount: 100,

forToday: 850

});

});

it('Spends amount bigger than the limit for today', () => {

testSpendWithActiveBudget({

amount: 1000,

forToday: -50,

newDayLimit: '944,44'

});

});

});The testSpendWithActiveBudget function takes over the checking algorithm. It makes a spend, checks that the spend is recorded, then checks to see if the amount for the day should have been recalculated. If so, it checks the new amount for the day. If not, it checks the balance for today—the difference between the daily limit and the amount spent today.

const testSpendWithActiveBudget = ({ amount, forToday, newDayLimit }) => {

spendMoneyOnce(amount, 'unknown');

cy.lastRecordContains(amount, 'unknown');

// Spending is less than the limit for today:

if (forToday > 0) {

cy.counterContains(forToday);

}

// Spending is bigger, the app will recalculate the amount for the day:

else {

cy.counterRowContains('New daily amount', 0);

cy.counterRowContains(newDayLimit, 0);

cy.counterRowContains("For today it's all", 1);

cy.counterRowContains(forToday, 1);

}

};Changing Dates

Now we have to test how the budget and history behave when the app is launched in a day or a few days.

context('Tests next day settings', () => {

beforeEach(() => {

cy.login();

cy.enterApp();

cy.createBudgetWith(10000, 10);

});

});First, let’s check that the unspent money goes into the piggy bank:

it('Tests next day safe record', () => {

spendMoneyOnce(400);

cy.skipDay();

cy.safeRecordContains(550);

});Then, that the amount for the day remained the same, if the user did not go over yesterday’s limit

it('Tests next day limit after spend less than prev limit', () => {

spendMoneyOnce(400);

cy.skipDay();

cy.counterContains(950);

});And that the amount will decrease if the user is over the limit:

it('Tests next day limit after spending more than prev limit', () => {

spendMoneyOnce(1000);

cy.skipDay();

cy.counterContains('944,44');

});For these tests, we will need the skipDay command, which will tell the browser to substitute the time when requesting the date and time.

First I create a basic skipDays command which will take the number of days to skip and the point in time from which to count down. Inside the command runs cy.clock, which describes the time change.

The first argument we pass to it is the timestamp of the moment to which we want the clock to change. The second is the functions and objects that will be changed at runtime. We only need to substitute the object Date.

Between tests, it is not necessary to reset the time settings via restore, because Cypress does this itself. But if we run skipDays within the same test several times, we need to call restore to reset the previous settings.

The reload method reloads the page - as if the user logs in to the application after a specified time.

Cypress.Commands.add('skipDays', (count = 1, from = Date.now()) => {

cy.clock().then((clock) => clock.restore());

cy.clock(from + count * MSECONDS_IN_DAY, ['Date']);

cy.reload();

});

// Alias for cy.skipDays(1)

Cypress.Commands.add('skipDay', () => {

cy.skipDays(1);

});Results

The coolest thing about these tests is watching them work. Here is accelerated video with all tests in the project. Some of you can find there a real working password to log in to the app 🙃