Domain Modelling Made Functional. Part 3

Last time we read the second part of the book. We discussed the functional decomposition of the domain model and learned how to use types to reflect business requirements. At the end of the chapter, we wrote code that was both documentation and a compilable basis for implementing the system.

This time we will learn about functional composition, partial application, and monads.

Chapter 8. Understanding Functions

In this chapter, the author describes FP in general and its key concepts. In particular, what functions and functional composition are.

Functions Are Things

Everything that can be passed as input or parameter and given as result is a thing. Functions are also things, since we can pass them as arguments and return as results in F# (and TS/JS).

“Input Function” can be used in another function to reduce duplication and extract common actions. “Parameter Function” can “adjust” the operation of another function. “Output Function” can itself be “tuned” by different parameters.

If we add currying and partial application, we have a flexible mechanism for “tuning” the behavior of programs.

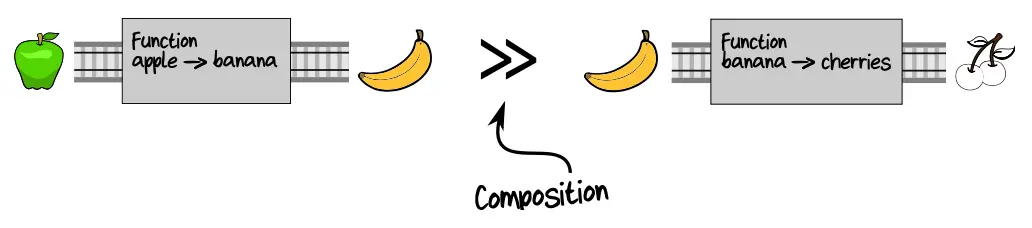

Composition

A function composition is the combining of several functions into a more complex function, where the output of the first function becomes the input of the next one. This combination of functions is called piping. It works if the type of the result of the first function is the same as the type of the argument of the next function.

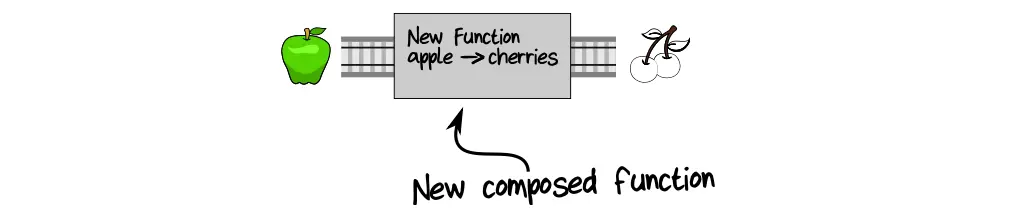

The example above is the same as:

…Because the result is the same. It does not matter to us what was in the middle of the process, it is the input and the result that are important.

Actually it is thanks to composition that we can build large applications from small functions:

Functions we can combine in services:

[low-level operation] >> [low-level operation] >> [low-level operation] => [service]

Services into processes:

[service] >> [service] >> [service] => [workflow]

Combining processes in parallel, we get an application:

[workflow]

[workflow] => [application]

[workflow]The main problem in composition is the mismatch between types of arguments and results. In the following chapters the author explains how to solve this problem.

Chapter 9. Implementation: Composing a Pipeline

In this and the next chapter we will implement the order taking process in code. We want to get something like:

let placeOrder unvalidatedOrder =

unvalidatedOrder

|> validateOrder

|> priceOrder

|> acknowledgeOrder

|> createEventsconst placeOrder = (unvalidatedOrder) =>

createEvents(acknowledgeOrder(priceOrder(validateOrder(unvalidatedOrder))));First we will implement each function separately, and then we will try to combine them into one big function. Along the way, we will learn how to manipulate data types so that the output of one function fits the input of the next.

In this chapter we will solve the problem that some functions require more parameters than the previous ones give them. And in the next one, we will solve the problem of different wrappers like Result, which prevent functions from being connected directly in a pipelining.

Using Function Types to Guide the Implementation

To let the compiler do all the type-checking work for us, we can specify the type for a function explicitly. That way, if we make an error in the parameters or the return result, we will know about it right away. In the example of a validation function, it might look like this:

let validateOrder : ValidateOrder =

fun checkProductCodeExists checkAddressExists unvalidatedOrder ->

// ^dependency ^dependency ^input

...const validateOrder: ValidateOrder =

(checkProductCodeExists, checkAddressExists, unvalidatedOrder) => // ...

// ^dependency ^dependency ^inputImplementing the Validation Step

For simplicity in this chapter we will discard the effects, so we will simplify the type of address checking for now:

type CheckAddressExists = UnvalidatedAddress -> CheckedAddress

// AsyncResult temporary gone.type CheckAddressExists = (address: UnvalidatedAddress) => CheckedAddress;

// AsyncResult temporary gone.The the validator type will be:

type ValidateOrder =

CheckProductCodeExists // dependency

-> CheckAddressExists // dependency

-> UnvalidatedOrder // input

-> ValidatedOrder // outputtype ValidateOrder = (

codeChecker: CheckProductCodeExists // dependency

) => (

addressChecker: CheckAddressExists // dependency

) => (

order: UnvalidatedOrder // input

) => ValidatedOrder; // outputTo create a validated order from an unvalidated order, we need to:

- Create a domain type

OrderIdfrom the unvalidated order string; - Create a domain type

CustomerInfo; - Create an

Addresstype fromShippingAddressand a second same type fromBillingAddress; - Put the constituent parts of the order together.

let validateOrder : ValidateOrder =

fun checkProductCodeExists checkAddressExists unvalidatedOrder ->

let orderId =

unvalidatedOrder.OrderId

|> OrderId.create

let customerInfo =

unvalidatedOrder.CustomerInfo

|> toCustomerInfo

let shippingAddress =

unvalidatedOrder.ShippingAddress

|> toAddress checkAddressExists // Helper with “injected” dependency

// ...And so on for every field of unvalidated order.

// When everything is checked, return the validated order.

{

OrderId = orderId

CustomerInfo = customerInfo

ShippingAddress = shippingAddress

BillingAddress = ...

Lines = ...

}const validateOrder: ValidateOrder = (

checkProductCodeExists,

checkAddressExists,

unvalidatedOrder

) => {

const orderId = OrderId.create(unvalidatedOrder.orderId);

const customerInfo = toCustomerInfo(unvalidatedOrder.customerInfo);

// Pass the dependency as the first argument:

const shippingAddress = toAddress(checkAddressExists, unvalidatedOrder.ShippingAddress);

// ...And so on for every field of unvalidated order.

// When everything is checked, return the validated order.

return {

orderId,

customerInfo,

shippingAddress

// ...

};

};The toCustomerInfo and toAddress functions are helper functions that will create domain types from unvalidated data or throw errors if the data does not fit. Inside them, we’ll use the same logic—convert unvalidated data into a domain, and if it fails, throw an error.

let toCustomerInfo (customer:UnvalidatedCustomerInfo) : CustomerInfo =

// Create properties for CustomerInfo,

// throw exceptions if data are invalid.

let firstName = customer.FirstName |> String50.create

let lastName = customer.LastName |> String50.create

let emailAddress = customer.EmailAddress |> EmailAddress.create

let name : PersonalName = {

FirstName = firstName

LastName = lastName

}

let customerInfo : CustomerInfo = {

Name = name

EmailAddress = emailAddress

}

// Return the result:

customerInfoconst toCustomerInfo = (customer: UnvalidatedCustomerInfo): CustomerInfo => {

const firstName = String50.create(customer.firstName);

const lastName = String50.create(customer.lastName);

const emailAddress = EmailAddress.create(customer.emailAddress);

const name: PersonalName = { firstName, lastName };

const customerInfo: CustomerInfo = { name, emailAddress };

return customerInfo;

};In the case of address verification, we also need to call a third-party service (dependency):

let toAddress (checkAddressExists:CheckAddressExists) unvalidatedAddress =

// Call the service dependency:

let checkedAddress = checkAddressExists unvalidatedAddress

// Use pattern-matching to get the value:

let (CheckedAddress checkedAddress) = checkedAddress

let addressLine1 = checkedAddress.AddressLine1 |> String50.create

let addressLine2 = checkedAddress.AddressLine2 |> String50.createOption

let city = checkedAddress.City |> String50.create

let zipCode = checkedAddress.ZipCode |> ZipCode.create

// Create address:

let address : Address = {

AddressLine1 = addressLine1

AddressLine2 = addressLine2

City = city

ZipCode = zipCode

}

// Return:

addressconst toAddress = (checkAddressExists: CheckAddressExists, unvalidatedAddress): Address => {

const checkedAddress = checkAddressExists(unvalidatedAddress);

const addressLine1 = String50.create(checkedAddress.addressLine1);

const addressLine2 = String50.createOption(checkedAddress.addressLine2);

const city = String50.create(checkedAddress.city);

const zipCode = ZipCode.create(checkedAddress.zipCode);

return {

addressLine1,

addressLine2,

city,

zipCode

};

};To create order lines, we’ll go through each non-validated item with List.map and do the same thing. But I suggest to see the code for creating order lines, as well as the implementation of the other steps and the creation of events in the original :-)

Injecting Dependencies

In functional programming, we don’t use DI containers, but instead keep all dependencies explicit. The book is introductory, says the author, so we won’t touch on things like Reader Monad and Free Monad. We’ll just “enforce dependencies” through a top-level function.

Let’s look at the helper example we wrote earlier:

let toAddress checkAddressExists unvalidatedAddress = ...

let toProductCode checkProductCodeExists productCode = ...const toAddress = (checkAddressExists, unvalidatedAddress) => // ...

const toProductCode = (checkProductCodeExists, productCode) => // ...The functions checkAddressExists and checkProductCodeExists are dependencies. When we use them in other functions, we must specify dependencies there as well:

let toValidatedOrderLine checkProductExists unvalidatedOrderLine =

// ^ Needed for toProductCode below.

let orderLineId = ...

let productCode =

unvalidatedOrderLine.ProductCode

|> toProductCode checkProductExists // Using the dependency.

...const toValidatedOrderLine = (checkProductExists, unvalidatedOrderLine) => {

// ^ Needed for toProductCode below.

const orderLineId = // ...

// We can partially apply functions that require such dependencies.

// Here this example is farfetched and useless, but it shows the technique in general:

const productCode = toProductCode(checkProductExists)(unvalidatedOrderLine.ProductCode)

// ...

}And so on, until we get to the “composition root”—the top-level function that will set up all these dependencies. Functions build in such a way are more convenient to test, because all dependencies are easy to replace, and the functions themselves do not contain states.

If a function has too many dependencies, you should consider whether you can simplify the function to get rid of some of them. If not, you could collect the dependencies into a record and pass them as a single argument.

If some things are only needed for one particular function, then such dependencies can be left out to the very top. When we pass one function to another, it pays to keep the type of that function as simple as possible.

Chapter 10. Implementation: Working with Errors

We want to create a consistent and transparent error handling scheme. In this chapter we will take a functional approach to error handling and learn how to separate domain errors from the rest.

Using the Result Type to Make Errors Explicit

A function signature must tell you about all possible results of its work explicitly. Therefore such a signature would be deceptive:

type CheckAddressExists = UnvalidatedAddress -> CheckedAddresstype CheckAddressExists = (address: UnvalidatedAddress) => CheckedAddress;We may have errors, and we want to display this directly in the type:

type CheckAddressExists =

UnvalidatedAddress -> Result<CheckedAddress,AddressValidationError>

and AddressValidationError =

| InvalidFormat of string

| AddressNotFound of stringtype AddressValidationError = InvalidFormat | AddressNotFound;

type CheckAddressExists = (

address: UnvalidatedAddress

) => Result<CheckedAddress, AddressValidationError>;Working with Domain Errors

We can divide potential errors into 3 groups:

- Domain errors are expected in the business processes themselves, such as an unaccepted order or lack of goods in stock;

- Exceptions (panics) lead the system to an unrecoverable state, such as out of array or lack of memory;

- Infrastructural error are expected from a technical point of view, but not by the business, like failed authentication or network problems.

Domain errors should be included in the domain model and covered by types. Exceptions should complete the process and be handled at the top level. Infrastructural ones can be handled either way, it will depend on the architecture and requirements. In this book, we focus only on domain errors.

We can type each error and then, for each process, collect a union of possible errors for that process:

type PlaceOrderError =

| ValidationError of string

| ProductOutOfStock of ProductCode

| RemoteServiceError of RemoteServiceError

...type ValidationError = string;

type ProductOutOfStock = ProductCode;

type RemoteServiceError = RemoteServiceError;

type PlaceOrderError = ValidationError | ProductOutOfStock | RemoteServiceError;This will not only be a piece of documentation, but will also make the error model extensible. We can’t immediately identify all bugs that may occur, so we need to think about adding more in the future. Union is great for that.

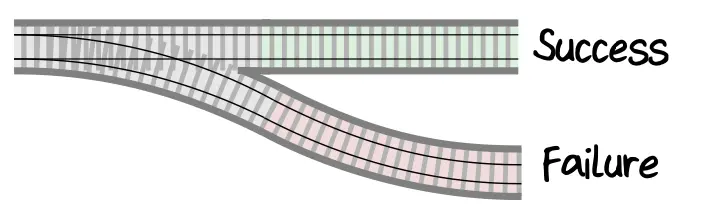

Chaining Result-Generating Functions

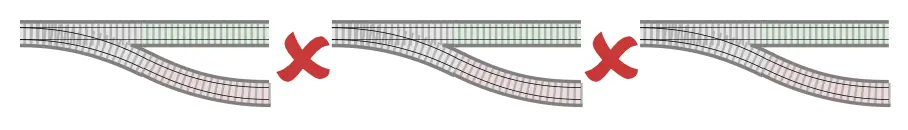

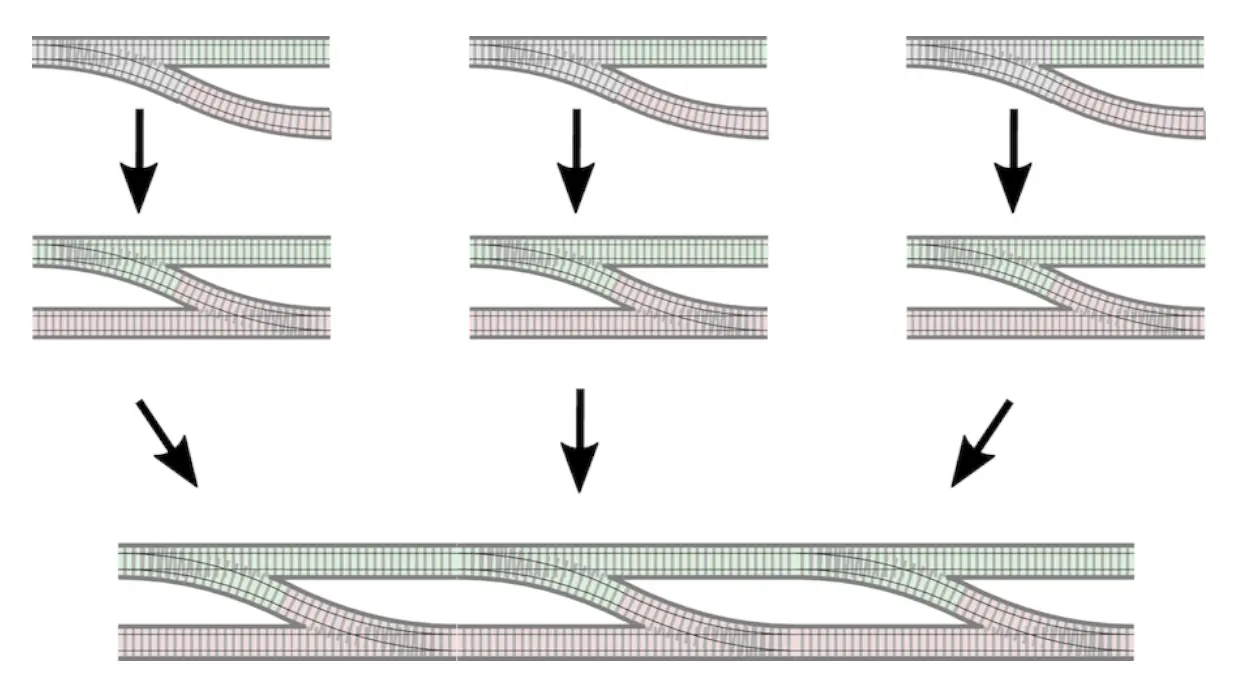

The problem with functions that return Result is that they are hard to put into a pipelining. It’s like they add forks to paths:

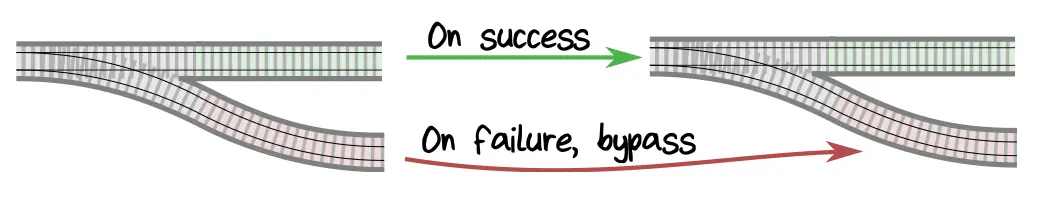

I want to make it so that if the “train has turned” on the wrong track, then further it only goes on that path:

But we can’t just combine the two Result-functions because they have different forms of inputs and outputs:

We want to get adapters that correct the “shape of the inputs” of Result-functions, so that they can be chained together:

One of such adapters is bind:

let bind switchFn twoTrackInput =

match twoTrackInput with

| Ok success -> switchFn success

| Error failure -> Error failureconst bind = (switchFn, twoTrackInput) => {

// The implementation in TS will strongly depend on the type system we build.

// We can check a special field or the whole structure,

// we may return the result in different ways in case of an error.

// Let it be as simple as possible for the example:

return twoTrackInput.ok ? switchFn(twoTrackInput.value) : Result.Error(twoTrackInput.error);

// Without pattern-matching of their types,

// you get a lot of boilerplate code

// and the solution still unreliable :-(

};Next, we can use map to handle the result. It will take the function it will execute on the result if there was no error. In case of an error, it will just return the error itself without applying the function:

let map f aResult =

match aResult with

| Ok success -> Ok (f success)

| Error failure -> Error failureconst map = (f, result) => {

// Here, too, we leave the implementation as simple as possible,

// but again, the specifics will depend on each case.

return result.ok ? Ok(f(result.value)) : Error(result.error);

};I skipped how to use bind, map and mapError, and F# constructs like let!, result {...}. I think it’s better if you read them yourself, looking at the code repository that comes with the book.

Monads and More

A monad is a pattern that allows you to chain monadic functions together. And a monadic function is a function that returns some “enhanced” value.

Technically, “monad” is a term for an entity that has:

- A data structure;

- Some related functions;

- The rules of operation of these functions.

In our examples, that structure was Result. To become a monad, it needs functions bind and return. We have already seen the first one, and the second one, that turns an ordinary value into a Result, is essentially a constructor of Ok.

Chapter 11. Serialization

The domain is good and all, but it has to communicate somehow with the infrastructure, which may not understand our types and in general be written in other languages. In this chapter, we will talk about how to serialize and deserialize data.

Persistence vs. Serialization

Persistence is the ability of a state to outlive in time the process that produced it. Serialization is the process of transforming domain-specific structures into a format that is easy to store (JSON, XML etc.).

Designing for Serialization

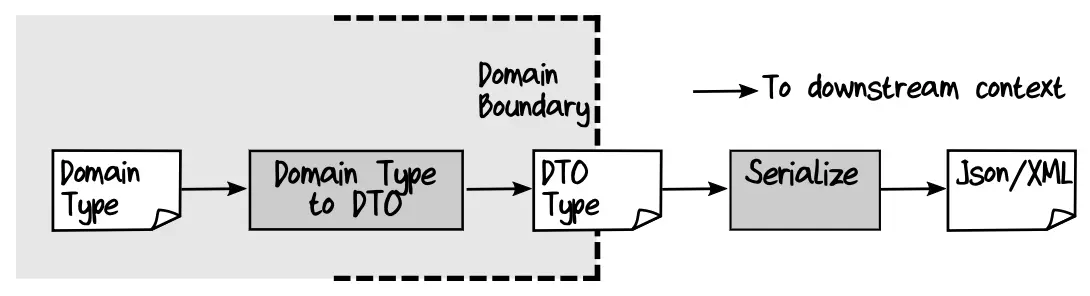

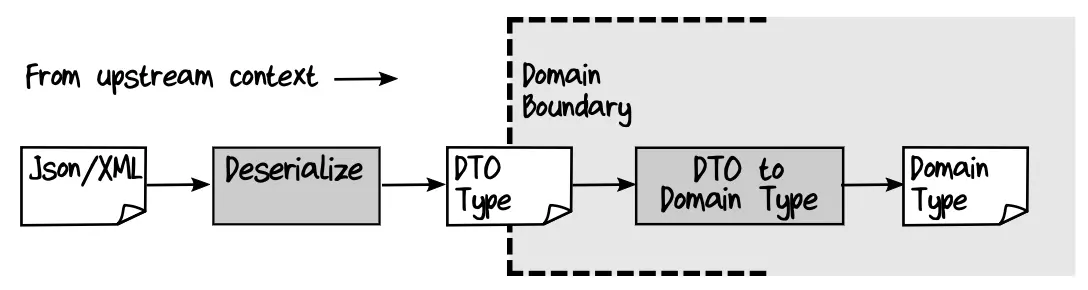

To make serialization painless, we need to convert domain objects into DTOs, and then serialize them. When deserializing, do the opposite.

A Complete Serialization Example

Suppose we want to figure out how to serialize the type Person:

module Domain =

// Assume, there's a limit 50 characters:

type String50 = String50 of string

// Assume, there's a range from 1/1/1900 and today's date:

type Birthdate = Birthdate of DateTime

// Domain type:

type Person = {

First: String50

Last: String50

Birthdate : Birthdate

}// Suppose we have a factory, which also does validation for this type,

// as we discussed in the previous part of the outline:

type BirthDate = DateTime;

type Person = {

first: FirstName;

last: LastName;

Birthdate: BirthDate;

};Next, let’s declare the type for the DTO and the functions that will convert the domain to DTO and back:

// DTO type with primitives without constraints:

module Dto =

type Person = {

First: string

Last: string

Birthdate : DateTime

}

// Module for converting between DTO and domain object:

module Person =

let fromDomain (person:Domain.Person) :Dto.Person =

// Get primitives from the domain type:

let first = person.First |> String50.value

let last = person.Last |> String50.value

let birthdate = person.Birthdate |> Birthdate.value

// Compose DTO:

{First = first; Last = last; Birthdate = birthdate}

let toDomain (dto:Dto.Person) :Result<Domain.Person,string> =

result {

// Validate and get typed values:

let! first = dto.First |> String50.create "First"

let! last = dto.Last |> String50.create "Last"

let! birthdate = dto.Birthdate |> Birthdate.create

// Create a domain object:

return {

First = first

Last = last

Birthdate = birthdate

}

}// DTO.ts

// DTO type with primitives without constraints:

type PersonDTO = {

First: string;

Last: string;

Birthdate: DateTime;

};

// Person.ts

// Module for converting between DTO and domain object:

function fromDomain(person: Person): PersonDTO {

const first = person.first;

const last = person.last;

// If necessary, we “extract” primitives,

// if the factory returns an object when creating it.

const birthdate = person.birthdate;

return { first, last, birthdate };

}Next, you will need to add a serializer which will turn the DTO into the format you want. I’ll leave this outside of the summary, there’s quite a lot of code, but it’s simple, so I recommend you look it up yourself.

How to Translate Domain Types to DTOs

There are several recommendations for “translating” types into DTOs:

- Simple types and aliases can be saved as the primitives they represent;

- Optional values can be replaced by

nullif they do not exist; - Collections—as arrays, mappings and other complex structures—as key-value structures;

- Records—as objects, with recursively applied these rules to each field;

- Unions, which are used as enums,—as number-values of those enums;

- It is better to avoid tuples in the domain, but if they exist, it is better to make a special record for them.

Chapter 12. Persistence

We designed the application so that it doesn’t care how its data is stored (persistence ignorance principle). But we still have to store it, so let’s talk about that too.

Pushing Persistence to the Edges

We want the domain logic to be pure, so we put it in the middle of the process and everything that has side effects around the edges. Let’s say we want to implement logic for invoice payment, where we need to:

- Load the invoice from the database;

- Make payment;

- If it was paid, mark it as paid in the database;

- If not, then mark it unpaid.

It is better to make the payment function clean and separate everything that is related to reading and writing to the database.

--- I/O---

Load invoice from DB

--- Pure ---

Do payment logic

--- I/O ---

Pattern match on output choice type:

if "FullyPaid" -> Mark invoice as paid in DB

if "PartiallyPaid" -> Save updated invoice to DB

--- I/O ---

Load all amounts from unpaid invoices in DB

--- Pure ---

Add the amounts up and decide if amount is too large

--- I/O ---

Pattern match on output choice type:

If "OverdueWarningNeeded" -> Send message to customer

If "NoActionNeeded" -> do nothingCommand-Query Separation

In FP, all objects are considered immutable, so let’s think of the repository as well. Every time we update something in it, it turns into a “copy with changes”.

In types we could express it this way:

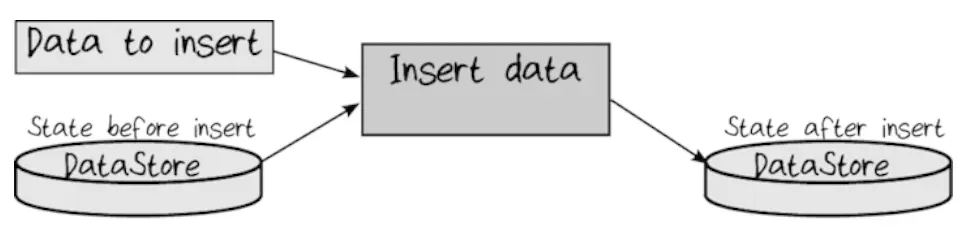

type InsertData = DataStoreState -> Data -> NewDataStoreState

type ReadData = DataStoreState -> Query -> Data

type UpdateData = DataStoreState -> Data -> NewDataStoreState

type DeleteData = DataStoreState -> Key -> NewDataStoreStatetype InsertData = (state: DataStoreState) => (data: Data) => NewDataStoreState;

type ReadData = (state: DataStoreState) => (query: Query) => Data;

type UpdateData = (state: DataStoreState) => (data: Data) => NewDataStoreState;

type DeleteData = (state: DataStoreState) => (key: Key) => NewDataStoreState;Here you can see that one of the signatures is different: ReadData returns data, and all others return the new state of the storage. That is, ReadData does not change the state.

This is the basis of the principle of command-query separation: CQS, Command-Query Separation:

- Functions that return data should have no side effects;

- And functions with side effects should not return data.

This principle leads to the following, CQRS, Command-Query Responsibility Segregation, which says that models for writing and reading data are better kept separate. The point is that the user object, for example, which is required for writing can (and most likely will) be different from the object which is returned for reading. Therefore, it is better to separate these models into different modules so that they can evolve independently.

Bounded Contexts Must Own Their Data Storage

There are a couple more recommendations on how to make persistence easier:

- Contexts should be able to change their data schemas without affecting other contexts;

- No one from the outside should be able to read data from any context’s storage.

This makes different contexts decoupled, allowing them to evolve independently of each other.

I offer concrete examples of working with different types of storages, writes, reads and transactions right in the book.

Rest Chapters

In chapter 13, the author explains and gives examples of how to keep the code clean when developing an application. What to do when new requirements arise, what to do when the old design needs to be changed, etc.

I didn’t summarize it because I would have had to copy the whole book 😃

I recommend reading this chapter (and the book itself) yourself.

Conclusion

It was interesting to me that I once came up with some of the principles in this book for myself. I used partial applications for “dependency management” and designing in types with separate types for different stages of the data lifecycle when I rewrote Tzlvt.

Functional pipelining and feature separation I used at my previous project even though the project was built in the OOP paradigm. The unrepresentability of invalid data is, of course, harder to design in TS because JS-runtime is breathing down my neck, but still, the idea was somehow sitting in my head. Some ideas I even used when I last redesigned my blog.

The ideas have proven to work, but now I also have an authoritative source to refer to on occasion 😃

What was new to me in the book was mostly about DDD and the initial stages of design. It wasn’t obvious that too abstract types could hurt in the beginning. And reading F# code was interesting, too.

All in all, the book is great—I recommend it.

Resources

- Domain Modelling Made Functional. Scott Wlaschin

- Part 1, Understanding Domain

- Part 2, Modeling in Types

Functional Programming Terms

Programming Languages

CQS, CQRS, and the Difference

- Command–Query Separation, CQS

- Command and Query Responsibility Segregation, CQRS

- Difference Between CQS and CQRS

- Command-Query Separation