Part 8. Adding New Feature

In previous posts, we wrote an application with one feature—a currency converter. In this post, we will add a new feature, implement it (in a bit simpler way than the previous one 🙃), discuss how to keep the coupling under control, and talk about the benefits of vertical slices.

Domain Model

Let’s say the product owner wants to conduct an experiment and add user notes to the application. We are not sure if this feature will stay in the application, so we want to add a quick solution that can be easily improved in the future if necessary.

To keep this post concise, we will describe only one use case: creating a note. This use case is a CRUD operation, and there is no domain logic involved. The entire process can be reduced to the following data flow:

// Get a string from the UI,

// if the string is valid,

// create a note object from it,

// save the data to the storage.

FormSubmitEvent ->

ContentString ->

Note ->

PersistenceThe input port for this use case will be of type CreateNote. It takes a string (potential note content) and starts an asynchronous saving process:

// core/ports.input

type CreateNote = (content: string) => Promise<void>;We will have only one output port for now, of type PersistNote. It takes the note draft, saves it to the storage, and returns the saved note:

// core/ports.output

type PersistNote = (note: DraftNote) => Promise<SavedNote>;The note data model will consist of 2 types: a note draft and a saved note. We’ll use a union type to make it easier to extend the data model in the future if necessary:

// core/types

type Note = DraftNote | SavedNote;

type DraftNote = { content: LocalizedString };

type SavedNote = { content: LocalizedString; id: EntityId };Also note that the note data should be internally consistent, so we will consider it an aggregate. In a simple case, this will not affect the code, but in the future, it may determine the choice of tools for the task.

Implementing Use Case

This time, we will not use “explicit composition” to implement the use case, but instead try to import modules directly:

// core/createNote

import type { CreateNote } from '../ports.input';

import { persistNote } from '../../infrastructure/persistence';

export const createNote: CreateNote = async (content: string) => {

const draft = { content };

await persistNote(draft);

};Despite the fact that composition is right in this file, we can still ensure that the use case relies primarily on the type, not the specific implementation:

// infrastructure/persistence

import type { PersistNote } from '../../core/ports.output';

// TODO: implement the port.

export const persistNote: PersistNote = async () => {};To test the use case, we can mock the infrastructure/persistence module and substitute the persistNote function with a spy.

Services and Output Ports

In the storage module, we explicitly indicate that the persistNote function should implement the PersistNote output port. This way, we ensure that services adapt to the application, and not the other way around. (Since composition in this feature is implicit, it is easier to make a mistake with the direction of dependencies, and we want to prevent it.)

Specifying the type in this case serves as a “buffer zone”: if we implement the port incorrectly, the compiler will flag it and prevent the application from being built. With all this in mind, inside the implementation, we can generally rely on libraries and tools directly:

// infrastructure/persistence

import type { NoteCollection } from '../../core/types';

import type { PersistNote } from '../../core/ports.output';

import { nanoid } from 'nanoid';

import { persist, retrieve } from '~/services/persistence';

export const persistNote: PersistNote = async (draft) => {

// Imagine the ID is assigned

// by the persistence service:

const note = { ...draft, id: nanoid() };

const notes = retrieve<NoteCollection>(persistenceKey) ?? [];

persist(persistenceKey, [...notes, note]);

return note;

};“Decoupling” libraries in the future will not be difficult precisely because of the reliance on types and the correct direction of dependencies.

UI and Input Port

A similar situation will arise with input ports. Components will rely on the CreateNote type, which will be implemented by the createNote function:

import { createNote } from '../../core/createNote';

import { useField } from '~/shared/ui/useField';

import { Input } from '~/shared/ui/Input';

export function NoteForm() {

const [value, update, clear] = useField('');

const onSubmit = useCallback(

(e: FormEvent) => {

e.preventDefault();

createNote(value);

clear();

},

[value]

);

return (

<form onSubmit={onSubmit}>

<label>

<span>Make a note:</span>

<Input type="text" value={value} onChange={update} />

</label>

</form>

);

}The composition is “mixed” with the component code, but ideologically it still “relies on abstraction” and is “sufficiently decoupled” from the application core.

In real projects, we’ll probably see code similar to this than the code we wrote in the previous posts because of import convenience and amount of “extra” code. The main idea, however, stays valid: when the application core is fairly decoupled from the UI and infrastructure, the project becomes more versatile.

Cross-Cutting Concerns

Suppose we want to add analytics to test a hypothesis. Based on the type of the use case, we can write a decorator that adds the analytics to the use case without interfering with the use case code:

// infrastructure/analytics

import type { CreateNote } from '../../core/ports.input';

import { sendEvent } from '~/services/analytics';

export const withAnalytics =

(fn: CreateNote): CreateNote =>

async (content) => {

sendEvent('NOTE_CREATED', `Content size of: ${content.length}`);

return await fn(content);

};Since the use case composition is located directly in its source code, we can apply the decorator right there:

import { withAnalytics } from '../../infrastructure/analytics';

// ↓ Decorator ↓ Use Case Function

export const createNote: CreateNote = withAnalytics(async (content: string) => {

const draft = { content };

await persistNote(draft);

});However, we still keep in mind that the decorator depends on the use case, and therefore we can separate them from each other. Conceptually, these two modules are decoupled and both rely on the type of the use case.

Using New Feature

To use the notes feature in our application, we can create a public API for it:

// ui/Notes

export function Notes() {

return (

<section>

<h2 className="visually-hidden">Notes</h2>

<NoteForm />

</section>

);

}

// notes/index

export * from './ui/Notes';…And add it to the dashboard:

// pages/Dashboard

import { Converter } from '~/features/converter';

import { Notes } from '~/features/notes';

export function Dashboard() {

return (

<>

<Converter />

<Notes />

</>

);

}In the dashboard component, it is visible how it composes widgets from different features together. This helps to visualize the “bounded contexts” for which each feature is responsible, and avoid their intersection, that is, to divide the entire application into so-called slices.

Vertical Slices

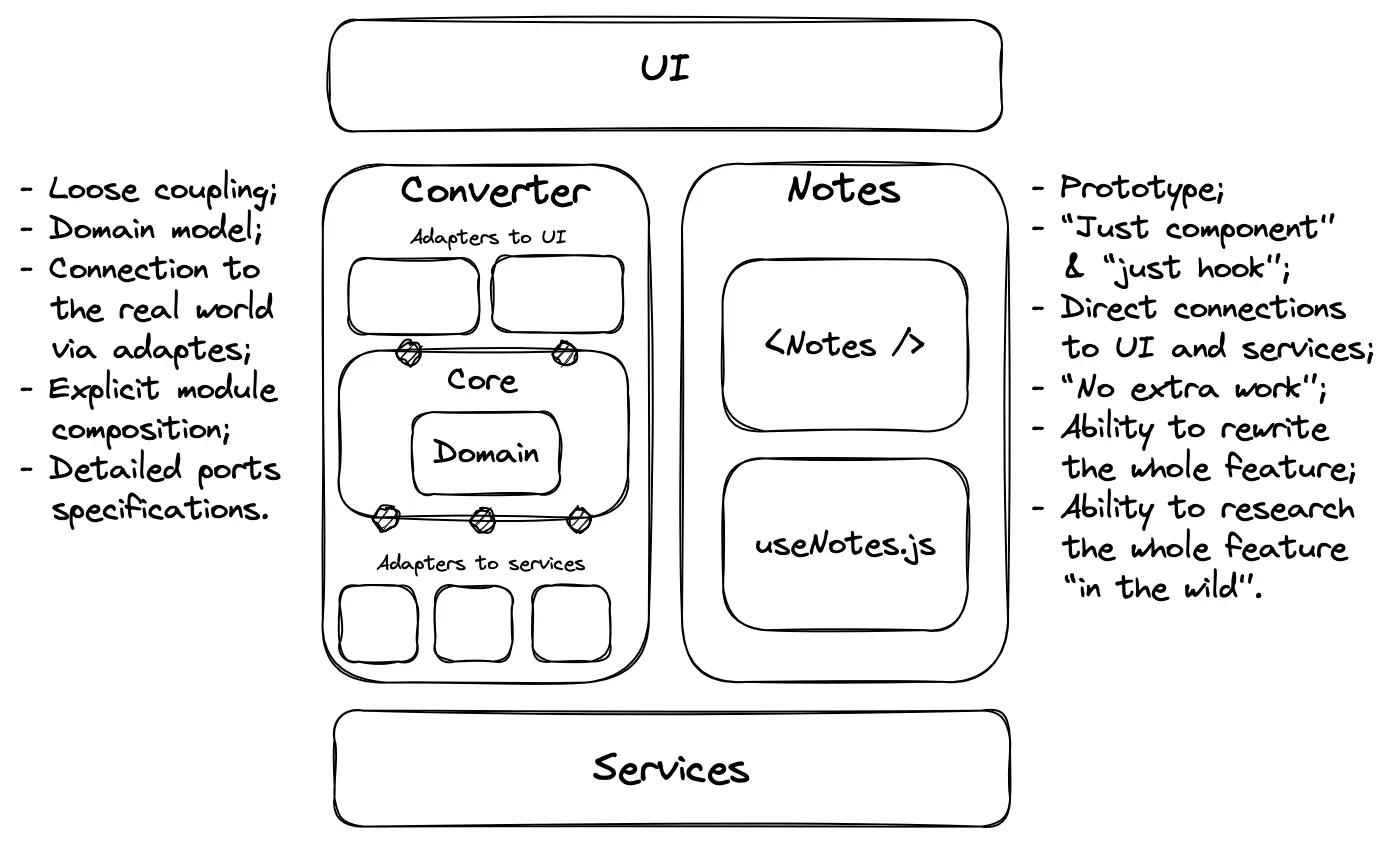

Each feature in our application describes one bounded context. It contains a domain model, code for use cases, input-output ports, and adapters to all the services it needs to work with. Another name for this part of the application is a slice.

The benefit of this architectural style is the independence and self-sufficiency of features. They can be added, removed, and developed independently of each other and with different levels of elaboration.

For a slice, it doesn’t matter how other slices work. In one slice, we can write code as cleanly and neatly as possible, while in another slice we can write code as if we were writing a prototype. We can split one slice into layers, while in another we can write all the code in one file.

Since slices are isolated from each other, solutions adopted in the code of one feature may not affect the code of other features. This makes it possible to add complexity in the code as needed. That is, we do not have to think through the “architecture of the entire application” as a whole, choose tools “all at once,” and become hostages to these decisions in the future.

Features may well have different structures, and their complexity may depend on the requirements and complexity of the domain. For a simple CRUD slice, we can write less tidy and simple code, while for a feature with complex business logic, we can outline the domain model, design use cases, and divide the code into layers:

Slices help us keep all the knowledge related to a particular subdomain together, without scattering it throughout the codebase. And isolation enables us to avoid making big decisions for the entire project.

In addition, slices force us to perceive data we work with differently. Since the focus of slices is on a specific part of the domain, we start seeing seemingly identical data through the prism of a specific subdomain. For example, the abstract concept of “price” in the context of procurement may come to mean “price from the supplier,” while in the context of sales, it may mean “the price on the label including shipping.”

This division helps us understand the essence of the data we work with, as well as the differences between “seemingly identical things” in the light of different parts of the domain.

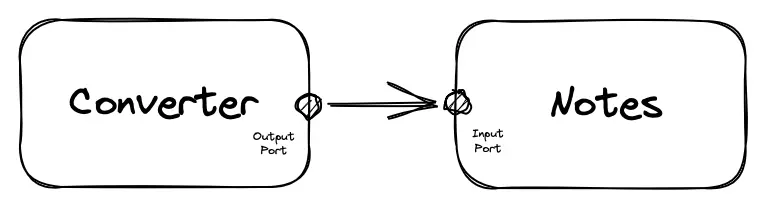

Feature Communication

The main idea of slices is their independence. Features in the application ideally should not know about each other’s existence and not affect each other’s work.

Proper context allocation and data separation between slices help achieve this. If we notice that we need data from another context, then we most likely divided them incorrectly. (This is especially noticeable if two features change with suspiciously equal frequency and operate with a similar set of data.)

However, for various reasons, full independence not always achievable, and we may need to configure communication between features. We can do this by either directly accessing one feature from another, or by using events.

In this post, we will look at an example of direct communication between features and discuss its pros and cons. In the next post, we will talk about event-driven communication and compare these two approaches.

Direct Communication Example

Let’s imagine we have a task to automatically create a new note with fresh exchange rates when updating them. (Yeah, it’s kinda far-fetched, but anyway 🤷)

To implement this, we need to “ask” another feature after receiving data from the server to create a new note. For the converter, this operation will be a signal to the “external world”. It is not very important to know exactly where we will send this command.

For the notes feature, such a signal is literally a lever on the input port that will launch the use case.

Such communication between features still increases their coupling because the converter will have to know about the existence of a neighboring feature. But by connecting them through ports, we still allow ourselves to decouple them in the future. (We will talk about this in the next post.)

Coupling via Ports

By coupling features through their ports, we create only one point of contact. This is convenient because it creates consistent expectations about how communication is organized between different parts of the application. We don’t have to think about where to look for the connection between different features.

In the case of notes, we already have an input port:

// notes/ports.input

type CreateNote = (content: string) => Promise<void>;The function that implements this port will be the entry point into the feature, and the code that will call it will run the use case, i.e. act as a “driving adapter”.

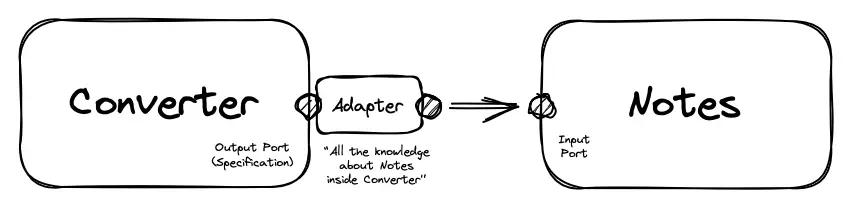

As for the converter, we will have to think about how to limit the spread of knowledge about notes and not let it “spread out” throughout the converter. For example, if we place CreateNote directly in the use case dependency, we will couple the core of the converter directly with the external world:

// converter/refreshRates

import type { FetchRates, ReadConverter, SaveConverter } from '../ports.output';

import type { CreateNote } from '~/features/notes/ports.input';

// Direct coupling... ↑

type Dependencies = {

fetchRates: FetchRates;

readConverter: ReadConverter;

saveConverter: SaveConverter;

createNote: CreateNote;

};…However, we would like to avoid this, because such coupling “smudges” the connection points between features, and knowledge about notes begins to spread throughout the converter code.

In addition, this option will encourage us to change the code of the converter when the logic of notes changes:

export const createRefreshRates =

({}: /*...*/ Dependencies): RefreshRates =>

async () => {

// ...

// In order to “serialize the note correctly”,

// we would have to modify the converter code:

const message = JSON.stringify(rates);

createNote(message);

// ...However, how to transform the note's content

// does not belong to the responsibility of the converter.

};To prevent the “spreading out” of knowledge about notes and maintain the independence of the converter use case, we will write an adapter to the notes feature.

Adapter to Feature? 🤨

The word “adapter” may suggest that this pattern is only needed to connect the application to third-party tools or services. But in reality, the task of the adapter is to make one some interface comparable to another some interface.

Both of these interfaces can be feature ports, which we will use. Let’s write the CreateNoteAdapter type for the converter. This type will be an output port because its task is to send a signal to the outside world:

// converter/ports.output

type CreateNoteAdapter = (rates: ExchangeRates) => void;The use case will only need to call the function implementing the CreateNoteAdapter type:

// converter/refreshRates

import type { CreateNoteAdapter /*...*/ } from '../ports.output';

type Dependencies = {

fetchRates: FetchRates;

readConverter: ReadConverter;

saveConverter: SaveConverter;

createNote: CreateNoteAdapter;

};

export const createRefreshRates =

({}: /*...*/ Dependencies): RefreshRates =>

async () => {

// ...

// All the use case has to worry about

// is calling this function and passing it fresh rates.

// Everything else, it promises to take care of.

createNote(rates);

};Then, all the knowledge about how to work with notes, what to convert them to, how to serialize them, etc. will be located in the implementation:

// converter/adapters

// The adapter depends only on the output port of the converter

// and the input port of the other feature:

import type { CreateNoteAdapter } from '../../core/ports.output';

import type { CreateNote } from '~/features/notes/core/ports.input';

// Accept one interface, return the other:

type AdaptInterface = (realFeature: CreateNote) => CreateNoteAdapter;

export const createAdapter =

(callFeature: CreateNote): CreateNoteAdapter =>

// Return a function that contains all the necessary information

// to correctly send a signal to the outside world

// and start the use case in the notes feature:

(rates) => {

const noteContent = JSON.stringify(rates, null, 2);

callFeature(noteContent);

};Partially apply the factory function by passing it the actual createNote function that implements the input port for notes:

// adapters/createNote.composition

import { createAdapter } from './createNote';

import { createNote as callFeature } from '~/features/notes/core/createNote';

export const createNote = createAdapter(callFeature);Now, the only place in the entire use case that is coupled with the code of another feature is the adapter and its composition:

This way, we create a foundation for an even deeper decoupling of features in the future.

Adapter Registration

We now need to register the created adapter in the use case composition and cover it all with tests. Let’s update the composition:

// converter/refreshRates.composition

// ...

import { createNote } from '../../adapters/createNote';

export const refreshRates: RefreshRates = withAnalytics(

createRefreshRates({ createNote /* ...Other dependencies. */ })

);Then, update the tests composition:

const fetchRates = async () => ({ ...rates });

const readConverter = () => ({ ...converter });

const saveConverter = vi.fn();

const createNote = vi.fn();

const refreshRates = createRefreshRates({

fetchRates,

readConverter,

saveConverter,

createNote

});And let’s add a new test that verifies that when updating rates, the use case calls the adapter function with the correct arguments:

describe('when called', () => {

// ...

it('calls a note creations out of the fresh rates data', async () => {

await refreshRates();

expect(createNote).toHaveBeenCalledWith(rates);

});

});Next Time

In this post, we created a new feature and implemented it, looking at how we can develop and work on different modules with varying depths depending on the requirements. Additionally, we described the direct interaction between the slices of the application and left room for future improvements to reduce coupling. In the next post, we will discuss how to make slices even more independent using events and in which cases it can be justified.

Sources and References

Links to books, articles, and other materials I mentioned in this post.

Isolation, Coupling, and Cohesion

- Anti-corruption layer

- Bounded context

- “I NEED data from another service!”… Do you really?

- Create, read, update and delete, Wikipedia

- Inversion of control, Wikipedia

- Cohesion in computer science, Wikipedia

Architecture and Patterns

Vertical Slices

- Feature-Sliced Design

- Restructuring to a Vertical Slice Architecture

- Vertical Slice Architecture, not Layers!

- Vertical slice, Wikipedia

Data States and Transformations

- Make Illegal States Unrepresentable!

- Types + Properties = Software: designing with types

- Union Types in TypeScript

Table of Contents for the Series

- Introduction, assumptions, and limitations

- Modeling the domain

- Designing use cases

- Describing the UI as an “adapter” to the application

- Creating infrastructure to support use cases

- Composing the application using hooks

- Composing the application without hooks

- Dealing with cross-cutting concerns

- Extending functionality with a new feature (this post)

- Decoupling features of the application

- Overview and preliminary conclusions