Part 2. Application Core Design

Let’s continue the series of posts and experiments about explicit software design.

Last time, we discussed what a domain model is, its benefits, and how we can use functional programming, static typing, and DDD to simplify modeling. In this post, we will talk about how to design use cases and discuss how to integrate our application with the outside world without the need to rewrite a lot of code.

Data and Use Cases

Our domain model contains data transformations that occur inside the converter but does not describe how the application should interact with the user. To describe such interaction, we will create use cases.

Simply put, use cases are descriptions of what should happen when a user interacts with the application. They show what data the application will receive, how and where from, what domain function it will execute afterwards, and how it will present the result of the work to the user on the screen or in the CLI.

We can create such a use case, for example, for updating quotes and get something like:

Use Case: “Refresh Exchange Rates”

When the user clicks a refresh button:

1. The app gets fresh exchange rates from the API.

2. Finds currently entered base currency value.

3. Recalculates the quote value based on these inputs.

4. Shows the updated values on the screen.Note that while we describe the details of interaction with the API for obtaining exchange rates, we do not specify concrete functions for updating the UI. Right now, we are only outlining the sequence of actions, describing operations “at a high level.”

Levels of Abstraction

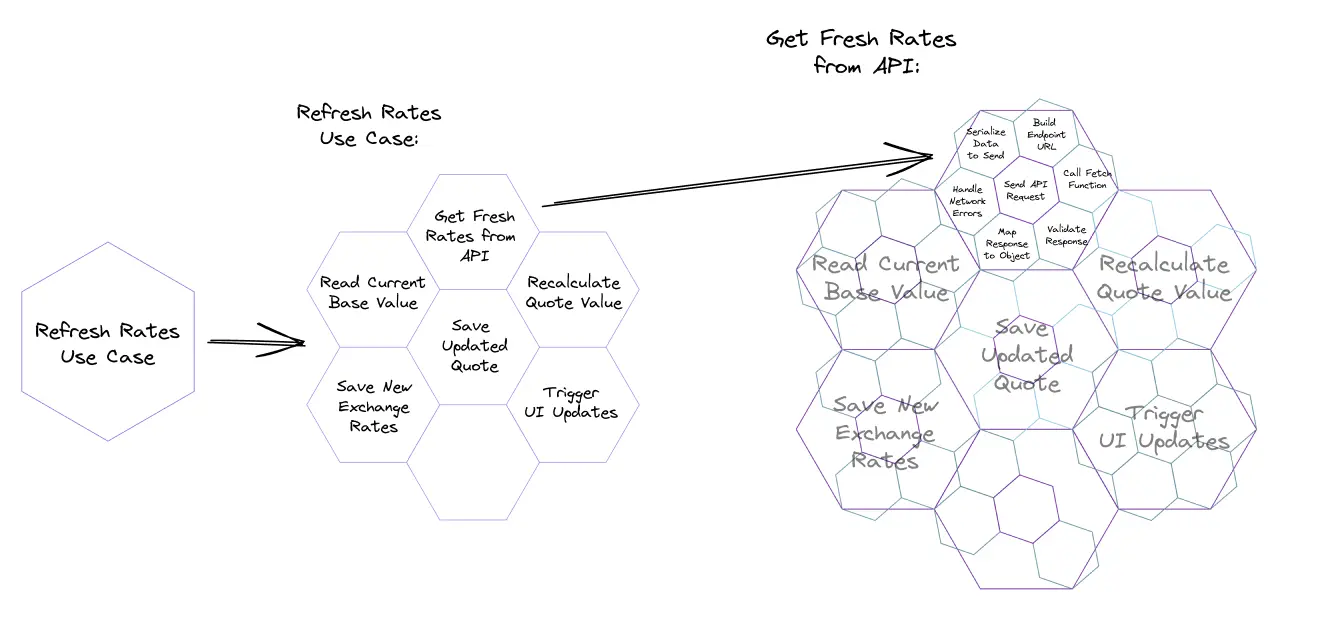

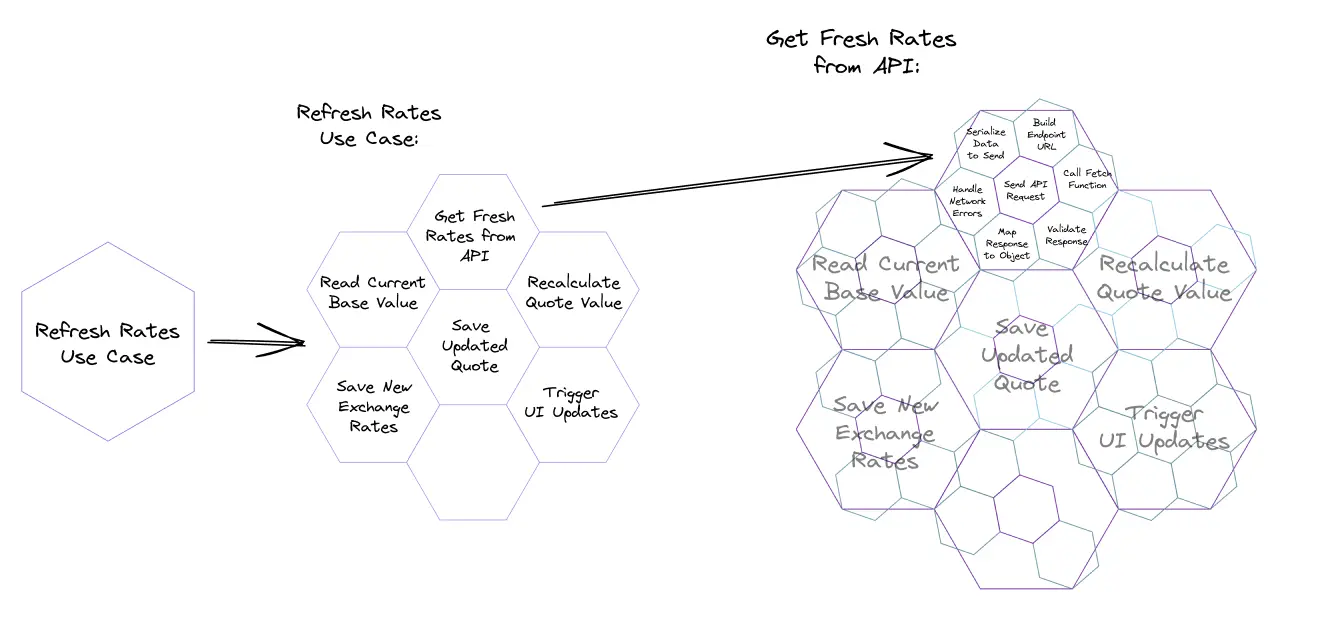

When I mention “design levels,” I like to refer to Mark Seemann’s post on “Fractal Architecture”.

In this concept, Mark presents programs as a set of nested hexagons. Each hexagon contains a limited number of components, but they can be zoomed in to see details. Thus, we keep a limited amount of information at each level, not overloading our heads:

I also like to use this metaphor when designing an app. Each level of a use case is like a hexagon. At first, we see only a “general description” of the operations that the application will perform.

Later, when we move on to implementation, we will “zoom in” to lower levels and work out each operation separately in more detail and depth.

Use Case as Types

Carefully examining the described scenario, we can notice that some of its operations can already be represented as types of the domain model:

Use Case: “Refresh Exchange Rates”

When the user clicks a refresh button:

1. The app gets fresh [ExchangeRates] from the API.

2. Finds currently entered [BaseValue].

3. Recalculates the [QuoteValue] based on these inputs.

4. Shows the updated values on the screen.If we take this further, we can represent the entire use case as a sequence of data transformations from the user input signal to displaying information on the screen:

ButtonClickEvent ->

ExchangeRates ->

[BaseValue, QuoteCode] ->

[QuoteValue, ExchangeRate] ->

DataRenderedEventWe will now try to express this sequence in the function code below.

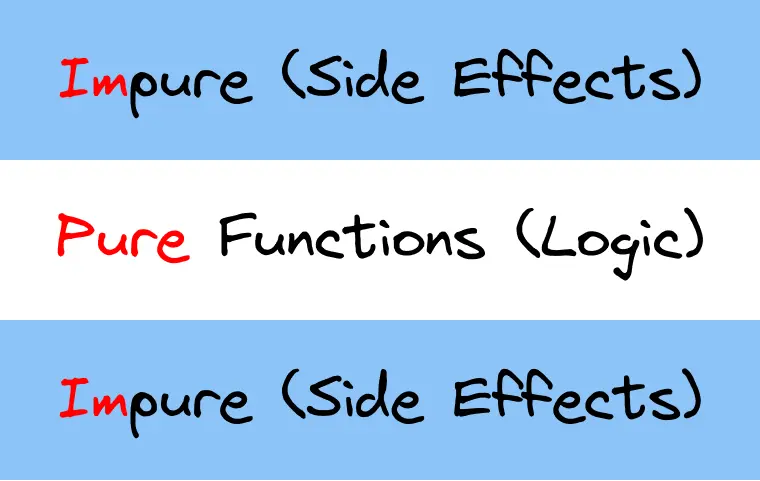

Impureim Sandwich

In the use case above, you may notice that interactions with the outside world (ButtonClickEvent and DataRenderedEvent) are located at the beginning and end of the use case, while only domain data transformations are in the middle.

This code organization is called “Functional core in an imperative shell”, or “Impureim sandwich”. Its essence is to concentrate all “impure” code at the edges, and keep only data transformations built on pure functions inside:

The main benefit of the sandwich is that it removes the influence of unpredictable effects on the data we work with. However, in our use case, there are a few more benefits:

- Since the “entry into the domain” is explicit, it is more convenient for us to validate the input data and check the invariants.

- The entire use case logic is reproducible and easily testable because it only depends on the input data.

- We don’t need to pre-plan how to interact with the outside world, but we’ll talk more about this a little later :–)

Designing the Use Case

When designing use cases, we can use the same approach we used when developing the model last time. First, we describe the functionality in types, and then we implement it as a function. Let’s go through all the stages of the use case and turn them into types.

Clicking on the button initiates the use case, after which we need to get exchange rates from the server, read the current value of the base currency, and the code of the quote currency. We can express these two operations as follows:

// Get fresh exchange rates from the API or a runtime data storage:

type FetchRates = () => Promise<ExchangeRates>;

type ReadConverter = () => [BaseValue, QuoteCurrencyCode];Then we pass the available data through the existing domain transformations:

// Transform data using the domain model:

type LookupRate = (rates: ExchangeRates, code: QuoteCode) => ExchangeRate;

type CalculateQuote = (base: BaseValue, rate: ExchangeRate) => QuoteValue;Finally, we display the result on the screen:

// Update the data in the UI:

type UpdateConverter = (rates: ExchangeRates, quote: QuoteValue) => void;Power of Abstraction

The described actions are easily held in our heads as a sequence because the type names are expressed in terms suitable for this level of abstraction. They do not delve too much into the details of each operation, but express its intent. Type names “package” all the complexity and details of each action, leaving only the most important information visible.

This approach helps us to dive into the code gradually, receiving information about the system in a controlled way, without overwhelming our working memory:

In addition, separating intention from implementation helps us to design use cases without thinking about the tools we will use. Instead, we roughly describe the functionality we want to obtain from the tools in the types.

This approach allows us to delay making big decisions about which libraries or third-party tools to use. The advantage is that we may not yet know all the actual requirements of the application, and it may be too early to choose tools. By abstracting away the tooling for now, we give ourselves a better chance to select the right tools in the future when we have a better understanding of how the application will work.

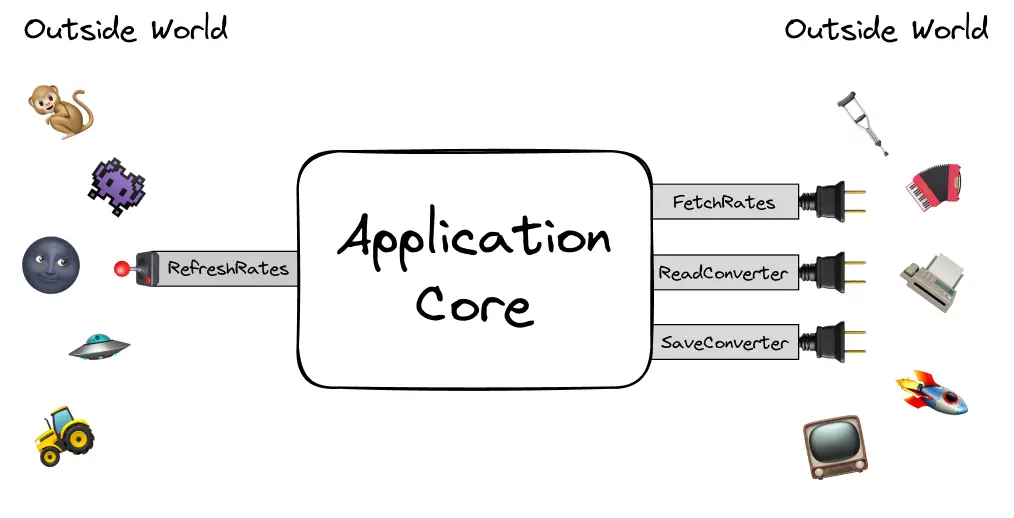

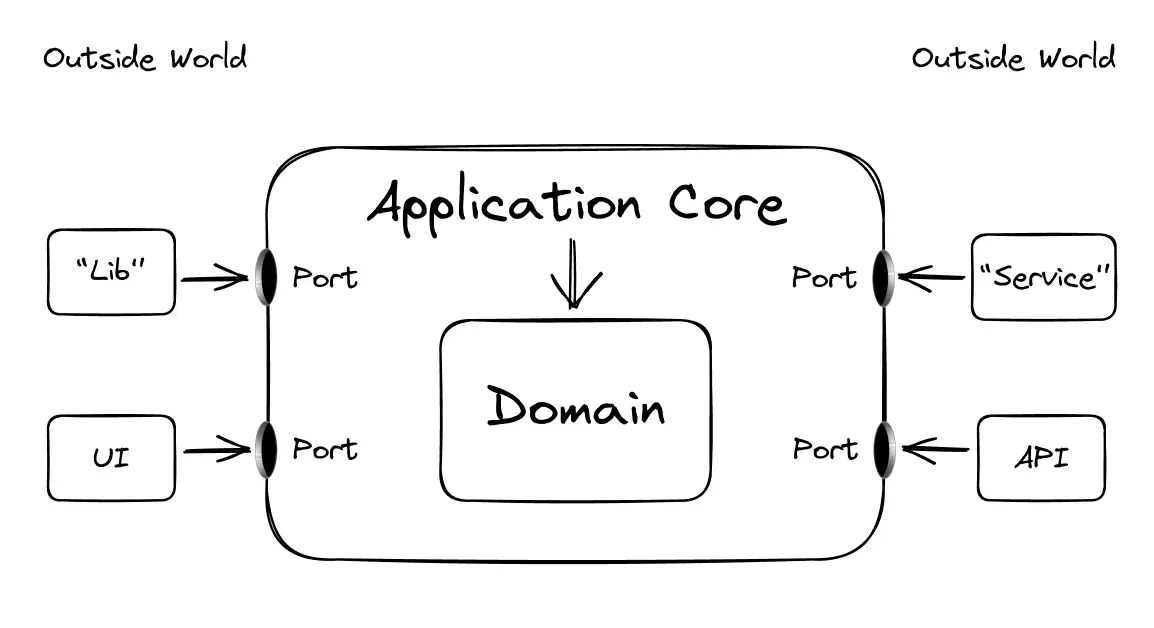

Application Ports

The types that “abstract out” libraries and third-party services are the so-called application ports.

A port is a specification of how an application wants to communicate with the outside world, how it wants to adapt the world to its needs. Ports describe how and in what form the application is ready to receive data and what result it will provide to the outside world.

The ports through which the outside world addresses the application are called input ports. And those through which the application talks to the outside world are called output ports.

The first ones describe what needs to be done to “push” the application do some work, while the second ones describe how the app will “initiate the contact” itself and what additional functionality it may need.

For example, in the case of updating exchange rates, the output port to the application would be some button-click handler function:

// This type says: “When the user clicks the button,

// the application will start an asynchronous process.”

type RefreshRates = () => Promise<void>;The output ports would be the types describing the server and data storage that would keep the previously loaded data:

// Network & API:

type FetchRates = () => Promise<ExchangeRates>;

// Runtime storage:

type ReadConverter = () => ConverterModel;

type UpdateConverter = (patch: Partial<ConverterModel>) => void;We can think of these types as the “levers” and “slots” that the “application box” provides to the outside. All interaction with the outside world will go through them:

Clear application boundaries and rules for communicating with it abstracts the details of the infrastructure and UI. A “buffer zone” appears between the application and third-party modules, which helps limit the propagation of changes from the application to the outside world and vice versa.

Abstraction-Driven Implementation

Like last time, having described the functionality in types, we can proceed with the implementation of the use case as a function:

// core/refreshRates

export const refreshRates = () => {};Calling this function is the entry point into the application core from the UI. This means that this function implements the input port. Let’s make sure it implements the RefreshRates type:

// core/ports.input

export type RefreshRates = () => Promise<void>;

// core/refreshRates

export const refreshRates: RefreshRates = async () => {};

// The function must be asynchronous,

// because `RefreshRates` returns a promise.

// To ensure the function implements some type,

// we can explicitly specify its type with `:`.

// Then, if the types don't match,

// TypeScript will complain about it.The contents of the refreshRates function will be a description of the entire use case:

// core/refreshRates

import type { RefreshRates } from '../ports.input';

import { calculateQuote } from '../domain/calculateQuote';

import { lookupRate } from '../domain/lookupRate';

export const refreshRates: RefreshRates = async () => {

// 1. Fetch latest rates from the API:

const rates = await fetchRates();

// 2. Get the current model from runtime storage:

const model = readConverter();

// 3. Run all the domain data transformations:

const rate = lookupRate(rates, model.quoteCode);

const quote = calculateQuote(model.baseValue, rate);

// 4. Update the runtime storage,

// consequently triggering the rerender.

saveConverter({ rates, quoteValue: quote });

// *. If we were working not with React but with a lib

// that doesn't automatically track rerenders,

// we could trigger the rerender from here manually.

};Inside the use case, we rely on guarantees from the functions that implement the output ports: fetchRates, readConverter and saveConverter. Thanks to the types, we know what arguments each of them expects and what result we will get after the call:

// core/pots.output

type FetchRates = () => Promise<ExchangeRates>;

type ReadConverter = () => Converter;

type SaveConverter = (patch: Partial<Converter>) => void;We can replace the implementations of these functions with stubs for the first time so that the compiler does not complain about missing variables:

const fetchRates: FetchRates = async () => {};

const readConverter: ReadConverter = () => {};

const saveConverter: SaveConverter = () => {};Use Case Dependencies

The stub functions for the output ports help with the initial design, but that’s where their usefulness ends. We can use type reliance more extensively.

Imagine instead of separate functions we have an object in which all these functions are gathered together:

// core/refreshRates

type AllOutputPorts = {

fetchRates: FetchRates;

readConverter: ReadConverter;

saveConverter: SaveConverter;

};

const ports: AllOutputPorts = {}; /*...*/We don’t care exactly how the functions get into this object yet, so let’s just assume that they somehow end up there. Then we can refer to this object and get all the functions we need from it in the use case code:

// core/refreshRates

export const refreshRates: RefreshRates = async () => {

const { fetchRates, readConverter, saveConverter } = ports;

// ...Use case code.

};If we go a little further, we notice that we don’t have to keep the dependency object inside the function. We can pass it as an argument to refreshRates:

// core/refreshRates

export const refreshRates: RefreshRates = async ({

fetchRates,

readConverter,

saveConverter

}: AllOutputPorts) => {

// ...

};The ports are now in a closure of the refreshRates function, not in any particular object. This means that for refreshRates they are very real, but we don’t need to create stubs for the ports anymore. All dependencies of the refreshRates function are taken directly from its arguments.

However, we broke the guarantees of the RefreshRates type. According to this type, the refreshRates function should not require arguments, and now it needs an object with dependencies. Let’s fix this by adding a default value to the argument so it’s no longer required. (And update the type name as well.)

// core/refreshRates

const stub = {} as Dependencies;

export const refreshRates: RefreshRates = async ({

fetchRates,

readConverter,

saveConverter

}: Dependencies = stub) => {

// ...

};If you recognize in this Dependency Injection (DI), that’s pretty much it. More precisely, its near-functional counterpart.

Testing Use Case

“Dependency Injection” gives us the opportunity to test a use case without waiting for its dependencies to be ready. This is liberating, because we can distribute work, for example, between different teams or switch between tasks depending on priorities.

Obviously, we cannot write integration tests without real dependencies, but we can write unit tests. For example, let’s describe tests for the use case with exchange rates update. Let’s start with planning the tests with .todo:

// core/refreshRates.test

describe('when called', () => {

it.todo('should recalculate the quote value using the rates from the API');

it.todo('should update the exchange rates data with the one from the API');

it.todo('...');

});We will try to use output-based to test the use case, that is, to simulate the input and monitor the output of the function. Sometimes we will also use state-based testing, although it is less resistant to change.

To test the use case, we replace dependencies with stubs and mocks. We replace the functions that provide us some data with stubs that don’t contain complex functionality. To check the result, we will use a spy—a function that will monitor how and with what arguments it will be called:

// core/refreshRates.test

// Simple stubs provide input data:

const fetchRates = async () => ({ ...rates });

const readConverter = () => ({ ...converter });

// Spy checks the output calls:

const saveConverter = vi.fn();

// All the dependencies for the use case:

const dependencies = {

fetchRates,

readConverter,

saveConverter

};Then we’ll describe that as a result of the work the spy should be called with certain data:

// core/refreshRates.test

describe('when called', () => {

it('should recalculate the quote value using the rates from the API', async () => {

// As the result of the use case:

await refreshRates(dependencies);

// ...The spy must be called with this data:

expect(saveConverter).toHaveBeenCalledWith({ quoteValue: 5, rates });

});

});Since dependency types can be implemented by anything, it’s pretty easy to replace them with a stub or a mock. This way, we can test the use case function based on contracts.

I usually try to write my tests and functions so that my code contains as few mocks as possible and as many stubs as possible. This helps avoiding test-induced damage and also makes tests independent of the specific implementation of dependencies and the location of modules in the file system. But this is just my preference, your tastes in testing might differ 🙃

Default Dependencies and Composition

We mentioned above that passing dependencies as the last argument is not the best solution:

- The argument with dependencies, even if optional, still violates the function interface. We would like the function type to be unambiguous and forbid any invalid call.

- Dependencies get into a function in runtime, and since the argument is implicit, it’s easy to miss and forget to pass it. We would like all the “function preparations” to happen beforehand, and if there are no dependencies, the code won’t get built at all.

In a future post, we’ll see how to achieve all of this by partially applying functions and “baking” dependencies.

Intention and Implementation

If we look at the imports in the use case file, we see that the application core uses only domain functions and types of input and output ports:

// core/refreshRates.ts

// From ports, import only types:

import type { RefreshRates } from '../ports.input';

import type { FetchRates, ReadConverter, SaveConverter } from '../ports.output';

// From domain, import functions:

import { calculateQuote } from '../domain/calculateQuote';

import { lookupRate } from '../domain/lookupRate';The use case sort of abstracts away from specific implementations of the application ports, allowing them to be passed from the outside:

Intention: Composition: Implementation:

RefreshRates( RefreshRates(

FetchRates, fetchRatesFn, <- const fetchRatesFn = async () => {...},

ReadConverter, -> readConverterFn, <- const readConverterFn = () => {...},

SaveConverter saveConverterFn <- const saveConverterFn = (data) => {...}

) )

Declares dependencies, Configure work of the function

that can be configurable. by passing specific dependencies.So the it becomes unimportant for the application core how exactly the ports to the outside world are implemented, as long as their interface is respected. We sort of break down the work of the use case into intention and implementation.

We express intention in types and code that relies on them. And we express the implementation in code that substitutes specific dependencies—composition. By doing so, we separate code with functionality from service code that “glues” different modules together.

Dependency Direction

The separation of functionality and composition helps the application core not to depend on third-party code: infrastructure, UI, networking. On the contrary, the application requires the outside world to “adjust” to its needs and depend on domain code and use cases:

This dependency direction, for example, makes it easier to replace tools in testing. In tests, we just replace the real service with a mock or stub:

// core/refreshRates.test

const saveConverter = vi.fn();

const dependencies = {

// ...

saveConverter

};

describe('when called', () => {

it('should recalculate the quote value using the rates from the API', async () => {

await refreshRates(dependencies);

expect(saveConverter).toHaveBeenCalledWith(/*...*/);

});

});This is a rather subjective argument, because services can always be mocked at module level. (Although it is also worth considering that module-level mocks can be more difficult to update, and they bind us to the file structure. What to choose depends on the problem.)

Full independence from the tools is not always necessary and justified, and in general it sounds utopian and maximalist. Sometimes it is much more effective to be bound to some library or service, especially if we are not going to change it. But since we’re experimenting and writing code “by the book”, we’ll close our eyes to that for now.

Other Use Cases

In addition to updating exchange rates, we have two more use cases: updating the value of the base currency and changing the quote currency. Let’s implement them as well, let’s start with the first one.

First, let’s declare the input port:

// core/ports.input

export type UpdateBaseValue = (value: string | number) => void;The function will accept a string or a number, which we will try to normalize to a base currency value. We commit to doing the normalization ourselves to ensure consistency of the data, because right now only the domain knows how to detect a valid value. We also free the module that will run this use case from having to worry about the value being passed.

Then we design the use case itself:

// core/updateBaseValue

export const updateBaseValue: UpdateBaseValue = (rawValue) => {

// 1. Impure section:

// 1.1. Get current `quoteCode` and `rates`.

//

// 2. Pure section:

// 2.1. Normalize the value received as an argument.

// 2.2. Determine the current rate of the selected pair.

// 2.3. Recalculate the quote currency value.

//

// 3. Impure section:

// 3.1. Save updated value of base currency.

// 3.2. Save the recalculated quote currency value.

};The pure section we can already build from domain functions:

// core/updateBaseValue

export const updateBaseValue: UpdateBaseValue = (rawValue) => {

// 1. Impure section:

// 1.1. Get current `quoteCode` and `rates`.

// 2.

const baseValue = createBaseValue(rawValue);

const currentRate = lookupRate(model.rates, model.quoteCode);

const quoteValue = calculateQuote(baseValue, currentRate);

// 3. Impure section:

// 3.1. Save updated value of base currency.

// 3.2. Save the recalculated quote currency value.

};And in order to retrieve and store the data, we will connect to the output ports:

// core/updateBaseValue

// Declare required dependencies:

type Dependencies = {

readConverter: ReadConverter;

saveConverter: SaveConverter;

};

export const updateBaseValue: UpdateBaseValue = (

rawValue,

// Get the dependencies inside the function:

{ readConverter, saveConverter }: Dependencies

) => {

// 1.

const model = readConverter();

// 2. ...

// 3.

saveConverter({ baseValue, quoteValue });

};And like last time, to avoid breaking the UpdateBaseValue type, let’s add a stub with the default value of the argument:

// core/updateBaseValue

const stub = {} as Dependencies;

export const updateBaseValue: UpdateBaseValue = (

rawValue,

{ readConverter, saveConverter }: Dependencies = stub

) => {

// ...

};Now we can write tests for this function by composing the use case with stubs and mocks:

// core/updateBaseValue.test

const readConverter = () => ({ ...converter });

const saveConverter = vi.fn();

const dependencies = {

readConverter,

saveConverter

};

describe('when given a valid base value update', () => {

it('recalculates the model according to the new value and current rates', () => {

updateBaseValue(42, dependencies);

expect(saveConverter).toHaveBeenCalledWith({

baseValue: 42,

quoteValue: 21

});

});

});

describe('when given an invalid base value update', () => {

it('recalculates the quote using 0 as the base value', () => {

updateBaseValue('invalid', dependencies);

expect(saveConverter).toHaveBeenCalledWith({

baseValue: 0,

quoteValue: 0

});

});

});Test-Driven Development

As in the case of the domain, we can use TDD as a design tool for use cases. Given that we rely on abstractions, we can describe our expectations without having to write real implementations of dependencies.

Let’s write the last remaining case with a change of quote currency, using TDD. Let’s plan out the desired behavior:

// core/changeQuoteCode.test

describe('when given a new quote code', () => {

it.todo('changes the quote code in the model');

it.todo('recalculates quote according to the new code and current rates');

});Let’s write a call to the first function and declare in which form we want to get the result:

// core/changeQuoteCode.test

const saveConverter = vi.fn();

const dependencies = {

saveConverter

};

describe('when given a new quote code', () => {

it('changes the quote code in the model', () => {

// After the function call:

changeQuoteCode('DRG', dependencies);

// ...We expect to see the change of quote currency in the model.

expect(saveConverter).toHaveBeenCalledOnce();

expect(saveConverter.mock.lastCall?.at(-1).quoteCode).toBe('DRG');

});

});Then we create an empty implementation and check that the test fails for the expected reason:

AssertionError: expected "spy" to be called once

20| it("changes the quote code in the model", () => {

21| changeQuoteCode("DRG", dependencies);

22| expect(saveConverter).toHaveBeenCalledOnce();

| ^

23| expect(saveConverter.mock.lastCall?.at(-1).quoteCode).toBe("DRG");

24| });

- Expected "1"

+ Received "0"Then we implement the function:

// core/changeQuoteCode

type Dependencies = {

saveConverter: SaveConverter;

};

export const changeQuoteCode: ChangeQuoteCode = (quoteCode, { saveConverter }: Dependencies) => {

saveConverter({ quoteCode });

};Then we will write the second test. This time we need to mix in some state and data, so we create another stub in the dependencies:

// core/changeQuoteCode.test

const readConverter = () => ({ ...converter });

const saveConverter = vi.fn();

const dependencies = {

readConverter,

saveConverter

};

// ...

it('recalculates quote according to the new code and current rates', () => {

changeQuoteCode('DRG', dependencies);

expect(saveConverter).toHaveBeenCalledOnce();

expect(saveConverter.mock.lastCall?.at(-1).quoteValue).toBe(2.5);

});After that, we check that the test fails because there is no value, and create an implementation:

// core/changeQuoteCode

type Dependencies = {

readConverter: ReadConverter;

saveConverter: SaveConverter;

};

export const changeQuoteCode: ChangeQuoteCode = (

quoteCode,

{ readConverter, saveConverter }: Dependencies

) => {

const model = readConverter();

const currentRate = lookupRate(model.rates, quoteCode);

const quoteValue = calculateQuote(model.baseValue, currentRate);

saveConverter({ quoteCode, quoteValue });

};Finally, let’s fix the broken ChangeQuoteCode input port interface and add a stub for dependencies:

const stub = {} as Dependencies;

export const changeQuoteCode: ChangeQuoteCode = (

quoteCode,

{ readConverter, saveConverter }: Dependencies = stub

) => {

// ...

};Next Time

In this post, we designed use cases and discussed how to connect our app with the outside world without depending on third-party services. Next time we’ll talk about how to implement application ports, what the difference is between UI and infrastructure from an application core’s perspective, and what to do if the outside world doesn’t work the way the application wants it to.

Sources and References

Links to books, articles, and other materials I mentioned in this post.

Books

- Clean Architecture by Robert C. Martin

- Code That Fits in Your Head by Mark Seemann

- Dependency Injection in .NET by Mark Seemann

- Unit Testing: Principles, Practices, and Patterns by Vladimir Khorikov

Dependency Management

- Dependency injection, Wikipedia

- Dependency Injection in .NET by Mark Seemann

- Dependency Injection with TypeScript in Practice

- Dependency inversion principle, Wikipedia

- Six approaches to dependency injection

Testing, Mocks, and Stubs

- Let’s speak the same language

- Mocking in Vitest

- Mocks for Commands, Stubs for Queries

- TDD: What, How, and Why

- Test-induced design damage

Abstraction, Composition, and effects

- Abstraction as a design tool

- Fractal hex flowers

- Functional architecture is Ports and Adapters

- Impureim sandwich

- Ports & Adapters Architecture

Other Concepts

Table of Contents for the Series

- Introduction, assumptions, and limitations

- Modeling the domain

- Designing use cases (this post)

- Describing the UI as an “adapter” to the application

- Creating infrastructure to support use cases

- Composing the application using hooks

- Composing the application without hooks

- Dealing with cross-cutting concerns

- Extending functionality with a new feature

- Decoupling features of the application

- Overview and preliminary conclusions