TDD: What, How, and Why

In April, I gave a talk about TDD on the Frontend Crew conference in Russian. In the talk I shared what TDD is, what its benefits are, and how to reduce friction to start using it in your project.

In this post, I pile up all main ideas from the talk, unfold each of them, and translate the text in English. If you want me to give this talk at your company or conference, please, let me know: bespoyasov@me.com.

Advantages of Testing

In the beginning, the frontend was simple, and there was no need to write tests. We designed pages, made forms, and sent data from them to the server. But then the frontend became complicated and it became clear that it was dangerous to code without tests.

Now having tests in on your project is a good sign. Writing code without tests is becoming smelly. Tests make development safer because they capture the current behavior of the system.

Tests Find Regressions

We people have very little RAM in our heads, we can’t keep the whole project system in it. Because of this, when we write code, we may not take into account how modules work or how they interact with each other. Especially if the system has a lot of stateful parts. Tests, on the other hand, catch errors we make because of this.

Tests are a Good Addition to Documentation

They describe how the system actually works. If we write in the documentation why it should work this way, then the tests tell us how it is “exactly this way”.

Tests Can’t Become Obsolete

If the tests are out of date, they fail. And if they fail, deployment should be blocked.

But tests, of course, have a cost…

Costs of Testing

They require time.

Time is needed for the tests themselves, and to determine the functionality to be tested, and to organize the infrastructure: how to generate fictitious data, how to organize access to mocks, etc.

In some projects we have no time: business can’t wait, deadlines are tight, you need it yesterday, developers fudge code without tests into production. It doesn’t happen everywhere, but where it does, it becomes hard to work. Tech debt and bugs accumulate, developers leave the project.

TDD Helps Solving These Problems

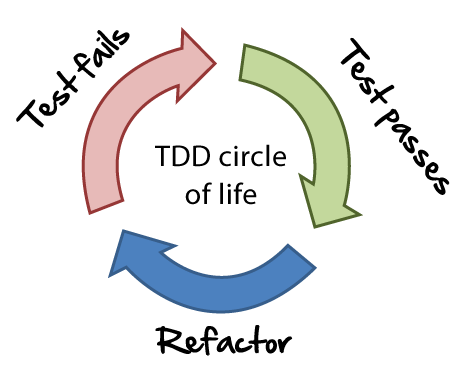

TDD (Test Driven Development) is built into the development process and ensures that the written code is already tested. The TDD development cycle consists of 3 stages.

The first stage is the red zone. On it, we write a test that will definitely crash with some reason. If the reason for the test falling down is not the same as expected, it is too early to move on to functionality implementation.

The second stage is the green zone. On it, we write a function that passes this test. The cycle is short, so the implementation should be as simple as possible.

The third stage is the blue zone. This is where we refactor the code of tests and implementation. Conducting refactoring in the blue zone is safe, because all the functionality that is affected by the refactoring is already covered by the tests. If something breaks along the way, we will know about it immediately.

Advantages of TDD

TDD is a kind of turns the development process inside out. Such a process has several advantages.

“Extra work” Problem Disappears

We write the tests right away, before we even start working on the entity code itself. By the end of the work, the tests are already written, we don’t have to put extra cognitive effort into making ourselves “write tests now 🙄”

Writing Tests and Refactoring Becomes a Habit

The TDD loop itself tends to it. Since in TDD we write the simple functionality after the test, we won’t be able to bring the function to the most convenient form without refactoring. We won’t be able to cover common cases without it either.

Refactoring Becomes Safer

The tests are already written 🙂

From the beginning, we kind of leave behind “bread crumbs” that will help us determine where and what broke if we screwed up during refactoring.

Different Entities Become Distinguishable

If a function has too many tests compared to the others, the function may be dealing with several tasks instead of one, and this is a violation of SRP.

API is Designed to be More Convenient

When we put ourselves in the shoes of the consumer of a function or class, we want the public API to be usable. In normal development we often get to the point of using it at the end of the job, and if the API isn’t convenient, it’s too expensive and lazy to rewrite it.

TDD puts us in the role of a consumer from the very beginning, even before we start working. We just have to immediately think about how this function will be used. And this is a powerful tool in design.

We can also share a draft of the function we are writing with our collaborators.

Costs of TDD

Like any tool, TDD has limitations and costs.

Need to Get Used to New Development Process

It doesn’t always work the first time. You might want to bang out a 20-line implementation and then write tests. TDD kicks in at this point and makes us turn our brains inside out. It’s uncomfortable at first, but it goes away after a while 😃

Allegedly “Encourages to Think Only of the Happy Path”.

I think this is a bit of a stretch, because you can think about happy path even when developing without tests, and when writing tests at the end.

You should rather get used to thinking in general about abnormal situations in which a function could find itself. That’s why I put the paragraph in quotes, because I think it’s not TDD’s fault.

Requires Time for Writing Tests

Tests still take time. Sometimes you still need a lot of time for tests, but now you have to put it into the development cycle from the beginning.

This is where you can ask me a question:

What do you mean from the beginning? And if I’m not the one setting the deadline, how do I change it? How do I explain why the deadline is suddenly changed? How do I convince the management that this is even necessary?

These are valid questions. Each of them is worth considering in terms of our influence:

- What we can influence directly,

- What we don’t always, indirectly or not ourselves,

- And what we can’t influence at all.

We’ll start with the simplest circle of influence and gradually get to the wider areas. What we can influence ourselves and immediately - directly our code.

How to Simplify Testing

In order for tests to take less time, they must be simple. And to make them simpler, there are several tricks.

Use Pure Functions More Often

Pure functions are those that produce no side effects. They always return the same result on the same set of arguments.

We don’t need a complex infrastructure to test pure functions. We just have to prepare the arguments and the expected result, and the test will only check to see if they match.

Even if you work in classical OOP, you can take advantage of pure functions if you use, as Mark Seemann calls it, functional architecture.

Avoid High Coupling

If the code is highly coupled, we have to create a lot of additional entities in the test, on which the module under test depends. When the code is loosely coupled, we can test modules in isolation.

Don’t Test Third-Party Code

It seems trivial, but sometimes tests may check that Math.random returns a random number, or that the library works as declared. We don’t need all that.

If we are working with a library, we should write adapter to it, and test it.

Use Handy Tools

The faster we see the results of the tests, the more seamless they are, the less friction will be caused by running them and waiting.

Put plugins for IDEs that run tests in the background, add filters for running tests in the console, and so on. Make it convenient for you and, if possible, have the tests run automatically when you start development, so there will be less friction to start writing them.

Create Convenient Infrastructure

Consider a strategy for storing and generating stub data and mock-objects, and discuss with your team how to handle large changes within types or functions. Ideally, the infrastructure should not be noticeable at all when working.

How TDD Helps Finding Smelly Code

Now let’s look a little wider: with TDD and tests we can improve the codebase as a whole, thereby gaining trust points from teammates and leads. If the codebase gets better from tests, this is both noticeable and useful.

When working with TDD specifically, we can pay attention to how the tests are written to the module to see if the code smells. Of course the first call is if there are no tests at all 😃

If there are no tests then you have to write them. But if there are, then pay attention to the following things…

Module Has Too Many Tests Compared to Others

Most likely, the module does several different tasks instead of just one.

It is worth seeing what tasks it solves, whether some of them can be put into separate functions, methods, classes, modules. In short, the module probably violates SRP, and its interface violates ISP.

Test Description Refer to Completely Different Domain Areas

Like we check the report generation, and expectation refers to sending a letter. The further and more incoherent the description, the more likely it is that we have merged several tasks into one.

Expectation isn’t Clearly Formulated

This sows doubts as to how the function should work at all. If the test cannot clearly and distinctly answer the question “What should happen and under what conditions,” then the code in the module isn’t clear either.

Test Preparation is Too Complex

For example, we have to create too many mocks, stubs, add some exotic infrastructure, request additional data. Most likely, abstractions have leaked in the module, or we messed up with dependencies somewhere.

Test Checks Implementation Details

We are doing extra work, probably screwing up dependencies again.

Tests are supposed to check the output of a function under given conditions. We pass the arguments, we check the result. If we’re checking how that result is obtained, then either we should do a public API review (rare) and split the method into several, or stop checking the implementation (most often).

Need to Mock the Library

We shouldn’t uncontrollably call libraries. We need adapters for them. Michael Feathers wrote about this in “Working Effectively with Legacy Code”. It is the adapters that we have to check.

For example, we can certainly mock useSelector when working with Redux-store, but if we move to another state-manager, then all such tests will have to be rewritten.

If we had our own hook that called useSelector, we would have to rewrite tests only for it. You can read more about this in Martin’s “Clean Architecture”, in the section about the adapters layer.

Tests Never Fails

The never-failing test is useless 😃

Not even that, such a test is harmful. We always need to make sure that test falls when the condition is unmet. If it doesn’t, then we can’t trust such a test.

How to Help Your Team Lead See Benefits

Okay, we are putting the code base in order. What else can we do?

We can go to a team lead and talk about TDD and testing. Chances are, the leads themselves know what all this is about. But if not, it’s worth looking behind the measurable parameters that can be improved with tests.

The parameters should be measurable, because talking about “Wouldn’t that be cool?” is not cool. We want to back up our point of view with facts: preferably ones that show exactly how the work affects the health of the project.

Of such parameters we can list:

- Bus Factor. If only one person knows about a project, that’s bad. The more people who know how things work, the more likely the project will survive and grow.

- Number of regressions. If you get a bunch of bugs in the alert monitor after every release, it’s a reason to wonder what’s wrong. We probably don’t take into account the complexity of the system when writing code.

- Documentation. Tests are a good addition to documentation but if there is none at all, it is better to start with tests.

- Time for refactoring. The more code is covered by tests, the less time will be spent on refactoring and rechecking the work afterwards. Refactoring will be much more pleasant, because you won’t have to sit and poke buttons with your hands for half an hour after each change.

If we measure the same parameters with tests, we can compare how much better they become. The results can then be used to support your point of view.

If we can’t find time to do that and everything is too bad, we can try and cover some code fragment with tests and make measurements on our own. Afterwards, you can come back and put the results of your ahem… research on the table and discuss them.

How to Help Business See Benefits

Not all developers can influence business decisions, but if they can, the rule is the same: always talk only about what can be measured and verified.

- You can use studies that have already been done. If it doesn’t work, do your own research.

- Compare the longevity of projects with and without tests, if you have such statistics in hand.

- Compare the average amount of time after which employees quit.

Important: all this works if the project is not a prototype. Prototypes have a different fate: to test a hypothesis and die. We are talking about a project that is going to live a long time.

Example of TDD

Let’s develop a little TDD application. Let it be a function that divides one number by another. (For more complicated examples I suggest reading my book TTT-TDD or see my talk on TDD in React. Both are in Russian, however, if you want me to translate them too, please, let me know: bespoyasov@me.com.)

I’ll use Jest as a test runner in the example. If you’re not familiar with its API, it has great documentation.

Let’s design tests and functionality.

- We want the function to basically divide one number by another;

- It also should round up a non-integer result to the 2nd decimal place by default;

- We should be able to specify a value for precision in the settings (for example, 3-4 decimal places);

- The function must not allow to divide by zero.

First Test

Since we are working with TDD, the first thing we need to do is write a test.

We want the function, when called, to return the result of dividing the first number by the second number. I like to describe the condition under which the function is called in describe and what exactly should happen in it. So we write it like this:

//index.test.js

// Condition:

describe("when called", () => {

// Expectation:

it("should return the result of division `a` over `b`", () => {Inside we write the code of the test itself. Good tests are simple, independent and concise, but apart from that they obey the 3-act structure “Arrange-Act-Assert”:

- In the first step, we prepare (arrange) everything we need for the test—arguments, expected result.

- On the second, we call (act) the tested function.

- On the third, we compare (assert) the expected result with the real result.

First we prepare the expected result, then we call the function and compare it.

// index.test.js

it('should return the result of division `a` over `b`', () => {

const expected = 5;

const result = divide(10, 2);

expect(result).toEqual(expected);

});Now test fails:

● when called › should return the result of division `a` over `b`

TypeError: (0 , _.divide) is not a function

15 | it("should return the result of division `a` over `b`", () => {

16 | const expected = 5;

> 17 | const result = divide(10, 2);

| ^

18 | expect(result).toEqual(expected);

19 | });…But we are not in the red zone yet. We remember that the test is bound to fall for the reason described in the expectation. We expect the function to return 10, but the test crashes because the function failed to import.

Red Zone

Let’s add a function and export it from the module:

// index.js

export function divide(a, b) {

return null;

}Check the test now:

● when called › should return the result of division `a` over `b`

expect(received).toEqual(expected) // deep equality

Expected: 5

Received: undefined

17 | const expected = 5;

18 | const result = divide(10, 2);

> 19 | expect(result).toEqual(expected);

| ^

20 | });

21 | });Now the test falls for the right reason. We check this to make sure that the test is testing our assumption and not something else.

Going to Green Zone

We can start the implementation. According to TDD, the implementation should be as simple as possible, even dead simple. This is necessary so that the development cycle takes no more than 10-15 minutes.

The easiest thing we can do is just return 5:

// index.js

export function divide(a, b) {

return 5;

}Test succeeds:

PASS ./index.test.js

when called

✓ should return the result of division `a` over `b` (2 ms)…But obviously, just returning 5 is not particularly useful 😃

We’ll refactor the function to make it work in a more general way.

Blue Zone and Refactoring

Let’s update the function:

// index.js

export function divide(a, b) {

return b / a;

}Test fails!

● when called › should return the result of division `a` over `b`

expect(received).toEqual(expected) // deep equality

Expected: 5

Received: 0.2

17 | const result = divide(10, 2);

18 | const expected = 5;

> 19 | expect(result).toEqual(expected);During refactoring we broke something: we divided the arguments in the wrong order.

That’s why TDD is useful, it covers our backs. Even if made a mistake, the feedback loop is so short that we instantly see where we made a mistake. Let’s fix it 🙂

// index.js

export function divide(a, b) {

return a / b;

}Great, the test passed, we can move on.

PASS ./index.test.js

when called

✓ should return the result of division `a` over `b` (1 ms)Extend Functionality

Let’s check how the function works with fractions.

Recall that we want the default function to round to the 2nd decimal place for fractional results. Let’s write it that way and form the expectation:

// index.test.js

describe('when the result is not an integer', () => {

it('should round it to 2 decimal places', () => {

expect(divide(10, 3)).toEqual(3.33);

});

});Test fails, let’s check the reason:

● when the result is not an integer › should round it to 2 decimal places

expect(received).toEqual(expected) // deep equality

Expected: 3.33

Received: 3.3333333333333335

24 | describe("when the result is not an integer", () => {

25 | it("should round it to 2 decimal places", () => {

> 26 | expect(divide(10, 3)).toEqual(3.33);

| ^

27 | });The reason is correct, we expected 2 digits, and we got a lot. So we’re in the red zone, moving on to realization.

Implementing Work with Fractions

Round up the result to 2 decimal places:

// index.js

export function divide(a, b) {

return (a / b).toFixed(2);

}The test didn’t get fixed, and the last one also fails now!

FAIL ./index.test.js

when called

✕ should return the result of division `a` over `b` (2 ms)

when the result is not an integer

✕ should round it to 2 decimal placesThe point is that toFixed returns a string, and we’re checking for a strict match.

TDD is also useful in that it reveals the strangeness of the third-party API when we start working with it. Let’s fix the implementation:

// index.js

export function divide(a, b) {

return Number((a / b).toFixed(2));

}Great, the test passes, we’re in the green zone, we can start refactoring.

PASS ./index.test.js

when called

✓ should return the result of division `a` over `b` (1 ms)

when the result is not an integer

✓ should round it to 2 decimal places (1 ms)Generating Tests

The test code is a code too, and we should pay just as much attention to it. Now we are testing one particular case of rounding, but we would like to cover different ones.

// index.test.js

describe('when the result is not an integer', () => {

it('should round it to 2 decimal places', () => {

// Testing only a single particular case:

expect(divide(10, 3)).toEqual(3.33);

});

});At the same time, you don’t want to write one-type tests that differ only in their arguments. Fortunately, we can generate tests automatically!

Let’s create an array, where each element will be an object with a test case. There will be arguments and expected result:

// index.test.js

describe('when the result is not an integer', () => {

const testCases = [

{ a: 10, b: 3, result: 3.33 },

{ a: 10, b: 6, result: 1.67 },

{ a: 10, b: 7, result: 1.43 }

];

});Now let’s iterate over each one and see if the test works:

// index.test.js

describe('when the result is not an integer', () => {

const testCases = [

{ a: 10, b: 3, result: 3.33 },

{ a: 10, b: 6, result: 1.67 },

{ a: 10, b: 7, result: 1.43 }

];

it.each(testCases)('should round it to 2 decimal places', ({ a, b, result }) => {

expect(divide(a, b)).toEqual(result);

});

});In the output:

PASS ./index.test.js

when called

✓ should return the result of division `a` over `b` (4 ms)

when the result is not an integer

✓ should round it to 2 decimal places

✓ should round it to 2 decimal places

✓ should round it to 2 decimal places (1 ms)

✓ should round it to 2 decimal placesIn general, we can go further and put the test data into a stub module. A convenient stub storage will allow us to use standardized data between different tests. This is especially useful if we have typed entities like user, product, etc.

Making Settings

Now let’s move on to specifying the settings.

// index.test.js

describe("when specified a precision", () => {

it("should round the result up to the decimal place specified in the settings", () => {From the consumption side of the function, it is immediately obvious that it would be better to use an object with settings rather than a number as a third argument here:

// index.test.js

// What's this 5?

// expect(divide(10, 3, 5)).toEqual(3.33333);

// That's better:

expect(divide(10, 3, { precision: 5 })).toEqual(3.33333);TDD is convenient because we use the function immediately, i.e. we can immediately see the API on the consumer side. If we wrote code first, we’d probably pass just a number as the last object.

Let’s write a function:

// index.js

export function divide(a, b, settings = {}) {

const { precision } = settings;

return Number((a / b).toFixed(precision));

}Some test fail now:

when the result is not an integer

✕ should round it to 2 decimal places

✕ should round it to 2 decimal places (1 ms)

✕ should round it to 2 decimal places

✕ should round it to 2 decimal places (1 ms)Oh, we don’t account for the object with the settings in the old calls—we broke backward compatibility!

// index.js

export function divide(a, b, settings = {}) {

// Round to the 2nd digit by default:

const { precision = 2 } = settings;

return Number((a / b).toFixed(precision));

}Now tests pass:

PASS ./index.test.js

when called

✓ should return the result of division `a` over `b` (2 ms)

when the result is not an integer

✓ should round it to 2 decimal places (1 ms)

✓ should round it to 2 decimal places

✓ should round it to 2 decimal places (1 ms)

✓ should round it to 2 decimal places

when specified a precision

✓ should round the result up to the decimal place specified in the settingsDivision by Zero

The last thing we want from this function is for it to forbid us to divide by 0.

// index.test.js

describe("when tried to divide by 0", () => {

it("should throw an error", () => {To check if a function throws an error, we need to wrap the call to that function in an additional function. Otherwise the error will crash the test, and that’s not what we need 😃

// index.test.js

describe('when tried to divide by 0', () => {

it('should throw an error', () => {

const attempt = () => divide(10, 0);

const error = new Error("Maths doesn't work like that...");

expect(attempt).toThrow(error);

});

});Let’s check the reason for the test failure:

● when tried to divide by 0 › should throw an error

expect(received).toThrow(expected)

Expected message: "Maths doesn't work like that..."

Received function did not throw

58 | const attempt = () => divide(10, 0);

59 | const error = new Error("Maths doesn't work like that...");

> 60 | expect(attempt).toThrow(error);

| ^The reason is correct, start implementing:

// index.js

export function divide(a, b, settings = {}) {

if (b === 0) throw new Error('Nope!');

const { precision = 2 } = settings;

return Number((a / b).toFixed(precision));

}Check if the test passes:

● when tried to divide by 0 › should throw an error

expect(received).toThrow(expected)

Expected message: "Maths doesn't work like that..."

Received message: "Nope!"

32 | export function divide(a, b, settings = {}) {

> 33 | if (b === 0) throw new Error("Nope!");

| ^We specified the error message incorrectly. Error checking is also a useful thing if we keep the stack clean and want the code to be easier to debug.

Let’s fix it:

// index.js

export function divide(a, b, settings = {}) {

if (b === 0) throw new Error("Maths doesn't work like that...");

const { precision = 2 } = settings;

return Number((a / b).toFixed(precision));

}Now the test passes.

Conclusion

Let’s see what we were able to achieve with TDD:

- The function works according to all the requirements we made at the beginning.

- We have a kind of “automatic” set of tests for it.

- Refactoring the code is safe because the tests cover the functionality we’ve already written.

- We design the API ahead of time, so it becomes easier and more convenient.

- We catch the oddities of third-party APIs early on, too.

Most importantly, all of these advantages appear as if “by themselves,” simply because the development process requires us to write the tests first.

The default implementation will be as simple as possible, because complex functions are harder to test. Since we have to do it in the beginning, we can immediately notice the extra complexity.

Resources

As usual, I’ve compiled a list of studies, books, and articles that I find most useful.

In addition to them, if you now Russian, I highly recommend reading my book TTT-TDD or see my talk on TDD in React. If you want me to translate these or translate this talk and give it at your company, please let me know bespoyasov@me.com.

Books and Articles

- Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

- Working Effectively with Legacy Code by Michael C. Feathers

- The Clean Architecture by Robert C. Martin

- Impureim sandwich